Can there be a liberally educated creationist?

Can a liberally educated person hold views on geopolitical conflicts based on his reading of sacred texts?

If a student at a faith-based institution gives up her faith, convinced that it's intellectually untenable, has that institution failed? Has it succeeded? What if that happens at a secular institution?

Whatever your answers to these questions, one thing is clear. Liberal education can interact powerfully with the spiritual and religious commitments and identities of our students. And so it should. Liberal education educates the whole person. All of us—whether at secular or faith-based institutions—have students in our classrooms for whom wholeness requires navigating the relationship between their spiritual lives and their education. We are necessarily involved in that process—whether we engage it explicitly or not.

- Must students' spiritual lives come under academic scrutiny? Or can they keep their faith separate from their academic lives and still be considered liberally educated?

- Might students of faith have to change some of their beliefs—beliefs, for example, affirmed by their religious community, but in tension with the best research and scholarship? Can we ask that of our students of faith? Can we not ask it of a liberally educated person?

- Or maybe it's not what students believe that matters, but how or why they believe what they do. Might there be some reasons for holding religious beliefs or some ways of holding them that are inconsistent with being liberally educated?

- Might the answers to these questions vary with our different institutional identities and missions? Or should we think that liberal education has the same goals whatever our institutional context?

All of us answer these questions, at least tacitly, in countless specific cases, whatever our own faith commitments and whatever the religious identity of our institutions. But we have very few opportunities for conversation about them, and the opportunities we do have are often confined to our individual institutions or faith communities.

That's a real loss. If liberal education teaches one thing, it's that thinking well requires thinking together, enriching our own perspective with those of others. "The Liberal Education of Students of Faith," the ninth annual Conversation on the Liberal Arts, held February 26 - 27, 2010, offered just that opportunity. For nearly a decade, the Conversation on the Liberal Arts has been bringing together faculty and academic administrators from the whole spectrum of American higher education, discovering how much we share, even as we learn from our differences. "The Liberal Education of Students of Faith" continued that rich tradition. Follow the links above to learn more.

The 2010 Conversation on the Liberal Arts is fast approaching. We're very much looking forward to the contributions you will make to our conversations. In fact we'd like to start the conversations now. Each of us comes to the relationship between liberal education and faith with our own questions and insights. We'd like to let your concerns shape our conversations as much as possible.

Broadly speaking the conference is concerned with the relationship between students' faith—whatever shape that might take—and the goals and practices of liberal education (the skills, knowledge, and intellectual virtues a liberal education instills and how it goes about that). Please take a moment and email us your questions, concerns and insights regarding this issue. Thanks for your contributions (and for indulging us in some editing) Here are some thoughts we have already received:

"What are the assumptions that we bring to the classroom about religious learners? How do we interact with these assumptions when teaching?"

"In what ways do students bring liberal learning to campus ministries, summer youth camps, mission work and community service or service-learning? How can we support them in making these connections between what they study and how they enact their faith?"

"One of the benefits of a liberal education is to teach one how to evaluate information without bias or emotion. Is it possible to include the unbiased study of religious faith in a liberal arts curriculum?"

"What themes resonate with our students as they wrestle with questions of faith: Perhaps grace, incarnation, community and vocation. Are there other themes that come to mind? How can we build some of these themes into core curricula or our majors in a way that is open to a variety of faith traditions (or students of no faith tradition)?"

"Faith is supposed to provide support in times of crises and indecision. Faith is supposed to help us perform when our abilities are questioned or weakened. What responsibility does the academy have in teaching students how to harness this faith? Should be train students to rely on faith or provide opportunities to support their expressions of faith within the structure of a liberal education? Positive psychologists tell us that faith can help mediate the effects of racism, sexism, and other "isms" on the psyche, resulting is positive performance. How do faculty and students harness this energy?"

"How does the liberal education inform their thinking on other faiths? For Christians, Jesus is seen as gateway...but what does this say to non-Christians, and what do our students think about faith as it

relates to global diversity?"

I have become interested in the issues that could be raised relating to an Islamic approach to the Liberal Arts. Exploring the role of reason and the liberal arts and how these manifested themselves historically in the Muslim context as well as in Europe are probably the best bridges that we can use to change the dynamic of Jewish-Muslim-Christian relations in the 21st century. We need to be intentional, dogged, and fearless to challenge the current paradigms that are falsely polarizing humanity.

In research done a few years ago, there were in the survey population about 20% of students from fundamentalist-evangelical backgrounds who were coming to college with determinedly closed minds. They came to school to "get smart" in order to get on with their lives. But on certain subjects they were unprepared to listen to professors and fellow students. My question, then: how do we teach these young people who intend not to be liberally educated by us? I do not favor being aggressive in deconstructing their worlds, but what are we to do?

"Neither a liberal arts education or faith development can take place without the depth that comes from the combination of time set aside for silence, active practice at listening, and regular time for personal and group reflection (not debates). How do we continue to hold back the tide of activities that work against a reflective life? How do we teach and practice liberal arts and spirituality in ways that hasten and deepen student ability to internalize and utilize the wisdom and experience of scholars, mentors, faith communities and colleagues?"

"How does a professor approach this topic pedagogically in a class composed of both religious and non-religious students (as well students who are only nominally religious)?"

"Most of our undergraduate students whom we meet do not seem to lose their faith, or have their faith weakened, by exposure to a liberal education.... The ones we encounter who do have crises of faith, due to their exposure to conflicting ideas, are mostly evangelical or fundamentalist Christians.... Over the course of my career I have had many encounters with students from conservative Christian backgrounds who came to the realization that they could not remain intellectually honest and reconcile biblical inerrancy, literalism, or religious exclusivism with what they were learning at the university.... The hard part for them is not intellectual.... The hard part consists of sometimes terrible consequences for most if not all of their most important relationships with their families and communities back home. The fear for their eternal salvation, the intense pressure put on them by family members and friends to conform, can be very painful for these students.... As a theologically and socially progressive Christian... a liberal education does not contradict my experience and practice of the faith; on the contrary, it enhances it. But as a pastor to students of all backgrounds at a university, I have learned to be very sensitive to the "cost of discipleship" for Christian students who adopt the form of the faith I practice, finding themselves suffering serious consequences with their families and communities as a result."

"The enduring question that we are asking has to do with identifying the markers of appropriate Christian commitment for members of our community as we seek to live with the tensions commensurate with our commitment to our Wesleyan-holiness heritage and our official relation to the Church of the Nazarene, our commitment to open inquiry and the liberal arts, and our increasing commitment to practically oriented graduate schools (business, education, nursing)."

"Are there ways of tying the school's mission to faith formation that are just plain inconsistent with the aims intrinsic to academic education?"

How are the life of the mind and the heart to be dealt with together? How is general education best enhanced by connecting with the work of both spiritual development and student development efforts?

"The concept of having a strong religious faith often blocks the student's willingness to embrace ideas which may be contrary to pre-disposed ideas and he/she is being exposed to in the classroom. What is our obligation toward that student in a liberal arts environment: do we back off or do we challenge the student's perceptions?"

Is introducing critical methodologies the correct approach to teaching scripture in Gen Ed, or should critical approaches be reserved for majors and upper-division courses? If the former, to what extent is the professor responsible for helping the student to "put the pieces back together" and form a constructive hermeneutic, and to what extent is this the responsibility of the student? Are professors merely responsible for introducing students to their disciplines, or are they also responsible for helping students deal constructively with the ways in which those disciplines interface with issues of faith and the life of faith? Or, another way, to what extent are scholars and professors also responsible for fulfilling a fundamentally pastoral task?

"Liberal arts education meets undergraduates at a point where they are finding that certain “givens†are being withdrawn and replaced by/converted into choices. Habits of churchgoing, family rituals and relationships of authority, schoolwork tasks and the like, all which are more involuntary than chosen, are being replaced by chosen/negotiated relationships on almost all fronts.... Within a span of just a few years, however, the involuntary dimensions of life will assume again their characteristic shape and demands.... These circumstances raise a host of questions for teaching the liberal arts. For example:

| • How may the articulation of faith perspectives best take the situation of 18-22 year old undergraduates into account? |

| • The "choice-emphasis" appears to provoke several kinds of response: some seem to be liberated and empowered, while others are confused and set adrift. How might a Christian liberal arts education [or any liberal arts education?] strengthen students' capacity to flourish?" |

"How do we assess this dimension of a student's educational experience and our attempt to fulfill this part of our mission? ("Our" refers to a school that has this as part of its mission, obviously)."

"If one's eternal salvation is staked on believing certain theological ideas to be true, then there is little emotional space for theological experimentation and innovation. Such students often feel like they are fighting for their lives when they encounter ideas that challenge their faith. These are the students I struggle hardest to help. They often cannot even begin to understand the course materials because they are filled with anxiety about what they are learning. So there is an affective challenge in teaching them that must be addressed before I have any hope of getting them to understand the new concepts I am introducing."

"Is there a significant difference between (on the one hand) a school's attempt to offer an education that is intended to mesh with and further religious values, and (on the other hand) a school that attempts to inculcate other values that are not as directly religious, such as environmental awareness and activism, volunteerism, wellness, etc.?"

"What happens when the student loses his/her faith as a result of successful challenges to one's classes? Do we have an obligation to support that student in any way?"

"Most students seeking a liberal arts education as their personal choice crave those transcendent ideas and experiences that enrich their worldly life. They study and perfect their discipline in Music, Art, History, Business, Technology along the whole range of disciplines, but their faith prompts the question, "Ad quid"? Crafting a liberal arts education that uses this realization as its compass will continue to refresh the polity with men and women who have an answer to that question. How do we craft a liberal arts education such that we teach students to be 'in the world' yet not 'of the world'?"

"Can schools which are rigid in their expectations of faculty "signing on" to various doctrinal tenets really model free, critical inquiry for their students in good faith? In other words, if there are distinct institutional pressures for faculty to adhere to certain beliefs, does that compromise the school's intentions to offer a place for students to critically examine their beliefs?"

"I think the way that faith is constructed in the way traditional students were reared has a profound effect on how successfully they encounter intellectual challenges without losing their faith. Â Students for whom faith is largely an assent to a set of propositions or dogmas are usually the most troubled. Â Students for whom faith is a matter of experience struggle the least."

"Is it possible to approach religion and religious belief from a position of neutrality? Or is a neutral position itself partly ideological?"

"Some students are gifted to inspire and lead others in faith due to their pronounced social skills development. Other students, not as highly developed socially, are yet gifted with an inner strength of faith that attracts less attention of the world but is nevertheless powerful. Therefore, it would seem then that a liberal arts education ought to comprehensively assist students at both ends of this spectrum in articulating their faith in themselves and in the world. How do we help students map their expression of faith to their particular skills, interests, abilities and temperament?"

"In cinema and literature, there are often issues regarding gender choices, language usages, sexual imagery, violence, etc—how does a teacher react to someone who judges literature and film from the perspective of prejudices inculcated in his/her religious upbringing?"

"I try to model for my more conservative students an intellectually honest but none-the-less genuine Christian faith. Probably the very conservative students find this suspicious or merely confusing, but it keeps the door open in a way that would not be possible if I taught the Bible without revealing my faith commitments to it."

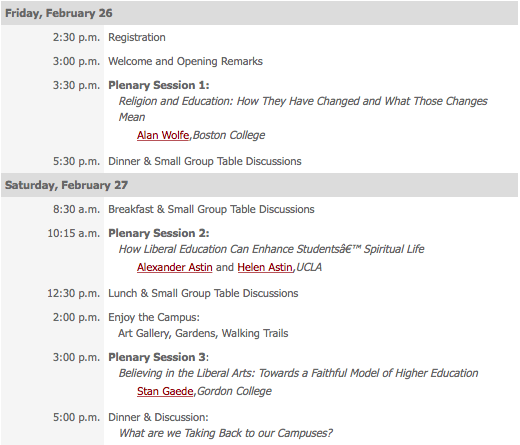

Religion and Education: How They Have Changed and What Those Changes Mean

Alan Wolfe, Boston College

How Liberal Education Can Enhance Students' Spiritual Life

Alexander W. Astin and Helen S. Astin, University of California, Los Angeles

Believing in the Liberal Arts: Towards a Faithful Model of Higher Education

Stan D. Gaede, Gordon College

| Friday, February 26 |

|

Welcome and Opening Remarks given by Westmont President Gayle Beebe |

|

Welcome and Opening Remarks given by Gaede Institute Director, Chris Hocekley |

|

Plenary Session 1:

|

|

||

| Saturday, February 27 | ||

|

Plenary Session 2: Keynote Address:

|

||

|

||

|

Plenary Session 3: Keynote Address:

|

|

Discussion Session lead by Westmont professor of Communication Studies, Deborah Dunn |