Back to Gallery

Jiuyang Zhu

Waiting for a Reconciled Day

Photograph on paper

2013

71.75 x 109.85 cm each

In the performance Waiting for a Reconciled Day the artist invited the parents of a murder victim, along with the parents of the convicted murderer to reconcile, to demonstrate the possibilities for love and forgiveness. It is a response to a criminal case that dominated the news and held captive the attention of the Chinese people for the better part of a year. The case was referred to as “10-20” by the Xi’an police, a brutal and seemingly senseless homicide of one college student by another that took place on October 20, 2010. Such events are not unique to China or the Chinese people, but are increasingly in evidence everywhere, including the United States. Zhu describes what prompted him to take up this subject in his work as follows:

Throughout the whole of human history, there has been violence between people of different ethnicities and of different nations—even between governments and their own people. The only way to escape this sort of pain is forgiveness and reconciliation….I saw the two sides fighting endlessly during the lawsuit, and felt that this event was no longer just a problem that remained between these two families, but rather an indication of a deep-seated socio-cultural problem. It was on face an event of collective violence, because the whole of society came to participate in it….I thought, the only way to leave behind the injuries one has suffered is forgiveness. But does this concept of forgiveness exist in our culture? What helps us understand the feeling of being forgiven? In the end, I decided to create this work.*

This incident is but one of far too many in recent years that have highlighted the growing insensitivity to the plight of others, the lack of remorse for wrongdoing and compassion for human frailty. It is a phenomenon that could be described as a corporate hardening of hearts. As Zhu explains:

In our spiritual lives, we are missing a form of love that goes beyond the carnal. If we each judge others from a position of moral superiority, by what standards do we determine our own righteousness? In our culture, we typically mourn the victim and hate the murderer. We lack the ability to feel sorry for both victim and murderer at once. Yu Hong once wrote, “We lack a conviction that all life is of equal value.” If it’s not possible to popularize such values, then is it even possible to have forgiveness in our lives? Why is our culture and society always trapped in a cycle of violence? We may be able to use hatred to bind the wound, but within there is still decay.

The victim’s father agreed to participate in the effort to reconcile, feeling, in Zhu’s words, “that reconciling with people was always a good thing to do,” while the perpetrator’s father rejected all overtures to participate. The victim’s father is pictured waiting patiently in the hope that the other father will show up. He never did. “This work is not yet over—it won’t be until they reconcile,” says Zhu.

___________________________

*Zhu Jiuyang interview with Luo Fei on his blog on March 30, 2015.

The Declaration of the Blind

Video of performance

2015

Running time: 27 minutes

Stills from The Declaration of the Blind

For the performance Declaration of the Blind the artist invited five blind folk “rap” artists from northern Shanxi province to adapt the text of the United Nations “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” and its 30 provisions, into a traditional storytelling drama. It was performed in Shanxi dialect, a dialect incomprehensible to most in the audience, accompanied by humble folk instruments. There is a long tradition of blind storytellers in China, more common in the north going back to at least the 16th century, who combine music and speech in a highly dramatic form. The stories they tell are typically extremely entertaining and often humorous. The troupe had never heard of the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” before. Zhu observed, “Perhaps it is all best summed up in one of the lines they sang, ‘Well, there’s never equality any time.’” According to critic Luo Fei said, “It’s absurd and sacred at the same time….And its sanctity lies in [the storytellers’] effort to give voice to others in spite of their suffering.”

The Defense in the Wilderness

Video of performance

2015

Running time: 13:56 minutes

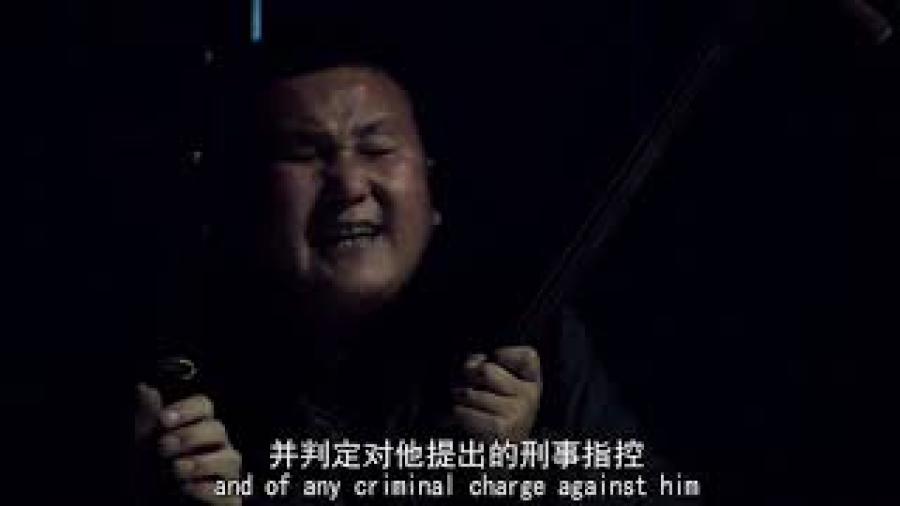

Stills from The Defense in the Wilderness

The performance The Defense in the Wilderness is set in the wilderness where there is a judgment seat, a prosecutor’s seat, a convict’s seat and a trumpet. A white tablecloth was on the table, and a red chair with high backrest was there, all ritualized and dramatized. The artist took on the role of a lawyer and pleads “not guilty” for an innocent lawyer held in prison.

Artists should actually return to the priesthood. And a priest is the one who stands between man and God, and between man and man. With this view in mind, I began to turn my eyes toward society, and use my art to reveal the different relationships between God and man, man and God, man and man, and man and nature, so as to contextualize the Christian faith within the reality in China and the traditional Chinese culture in my artistic creation.

—Jiuyang Zhu

About the Artist

Born in Wuqi County, Shaanxi Province in 1969, Jiuyang Zhu graduated from Xi'an Academy of Fine Arts in 1992. In 1991 he participated in the first Xi'an Youth Plastic Art Exhibition and won the first prize. Zhu converted to Christianity in 2004. Since 2005, he began to serve in the church and make art about faith. He has been invited to participate in numerous domestic and international art exhibitions. Zhu currently lives and works in Songzhuang, Beijing, China.