Back to Gallery Next Artist - Yongliang Wang

Jo-Ann VanReeuwyk

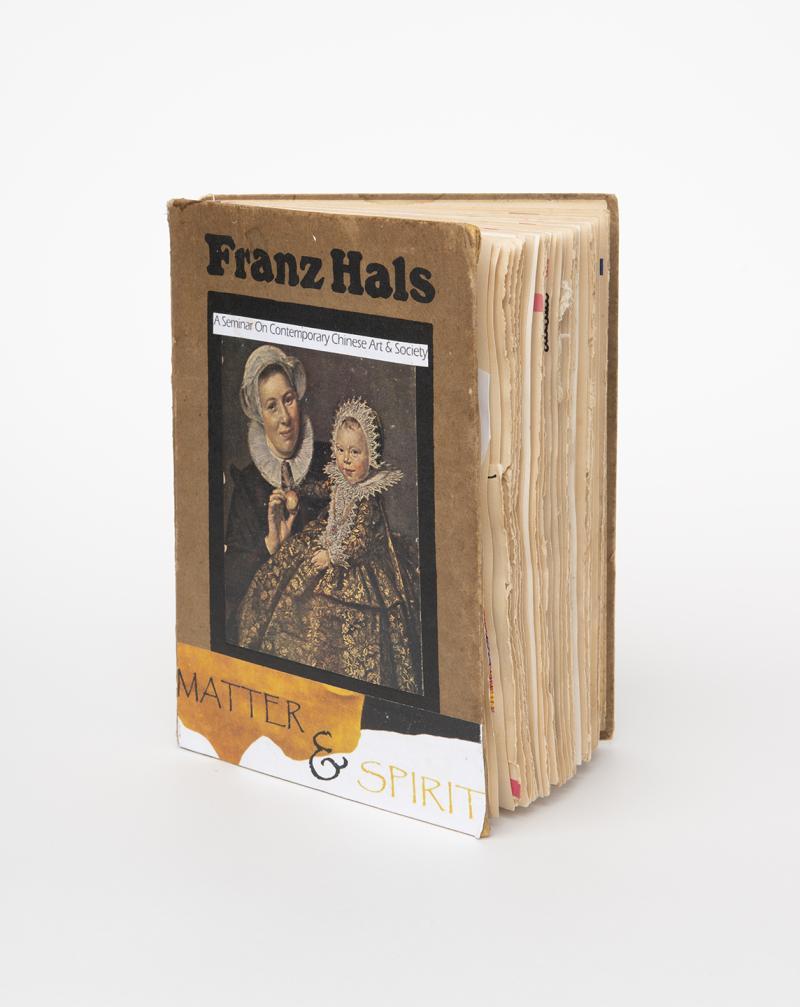

Portrait

Altered book

2018

21 x 15 cm

(detail of Portrait) |

|

Jo-Ann VanReeuwyk’s collaged book titled Portrait uses an old biography on the 17th century Dutch portrait painter Franz Hals as the ground for bringing together aspects of her experience in China with her Dutch heritage. It is a complex multi-layered “puzzle” of pieces inserted, glued, stitched together with mysterious and sometimes surprising juxtapositions whose picture is anything but clear. Like a person, it requires intent and prolonged consideration to unpack whatever significance resides there.

Zhishi Qingnian (Educated Youth)

75 x 70 x 2 cm

Zhongshan (Mao Suit)

85 x 70 x 2 cm

Fiber (teabag construction)

2019

I had always thought that clothing allowed for freedom and individuality. That began to change in the early eighties when I started to contemplate the burka and the hijab. While to me these articles of clothing appeared very restrictive, the women who wear them were expressing how they, in fact, provided freedom. Freedom from gaze, from expectations, from competition. Once I began teaching, I pondered the restrictions vs. the freedom that school uniforms afford. Would, in fact, these uniforms create that elusive value “equality”?

In China, it surprised me to learn that following Chairman Mao’s directive, the Chinese people eagerly took to wearing a uniform, the so-called “Mao suit” because it eliminated social and cultural inequality and provided an environment less concentrated on status. It had not raised complaints about reduced individuality and uniqueness as I had expected it would.

What became known as the “Mao suit” worn by Mao himself and others in power under him, was in actuality, a very different jacket from the one worn by everyone else. Derived from an earlier time, combining the Chinese tunic and Western dress, Mao’s jacket was full of symbolism and had unique attributes that included:

- Four pockets symbolizing the four virtues and the four cardinal principles of the classic text I Ching: Propriety, Justice, Honesty, and Sense of Shame.

- Five large buttons in the front of the jacket standing for the five branches of government: Executive, Legislative, Judicial, Control and Examination.

- Three smaller buttons on the sleeves representing the three principles of the people: Nationalism, People’s Rights, and People’s Livelihood.

These jackets were made of very fine wool. To this day the Mao suit persists. It has been appropriated by fashion designers and artists around the world. President Xi has re-claimed the suit as his own to wear to political and international events.

In contrast, the peasant jacket, as it is sometimes called, was made of rough materials and had no pockets. The front buttons still represented the five symbols but were very plain. Only the youth in the Red Guard were permitted any embellishment of the simple uniform, wearing red kerchiefs to identify them as “soldiers” for Mao. In addition, Mao’s “Little Red Book” was carried by all of the Red Guards and considered part of the uniform, raising the status of these youth that much higher.

After all of these years investigating this phenomenon, my question remains unanswered: what is the real purpose of a uniform?

—Jo-Ann VanReeuwyk

About the Artist

Jo-Ann Van Reeuwyk is a professor at Calvin University where she directs the Art Education program. She co-founded and directed the Artist Collab, a successful interactive and collaborative program for students in the arts at Calvin. She maintains a part-time fiber studio focusing on handmade paper and sculpture.