Back to Gallery Next Artist - David Young Cameron

Jacques Callot

Jacques Callot (French, 1592–1635)

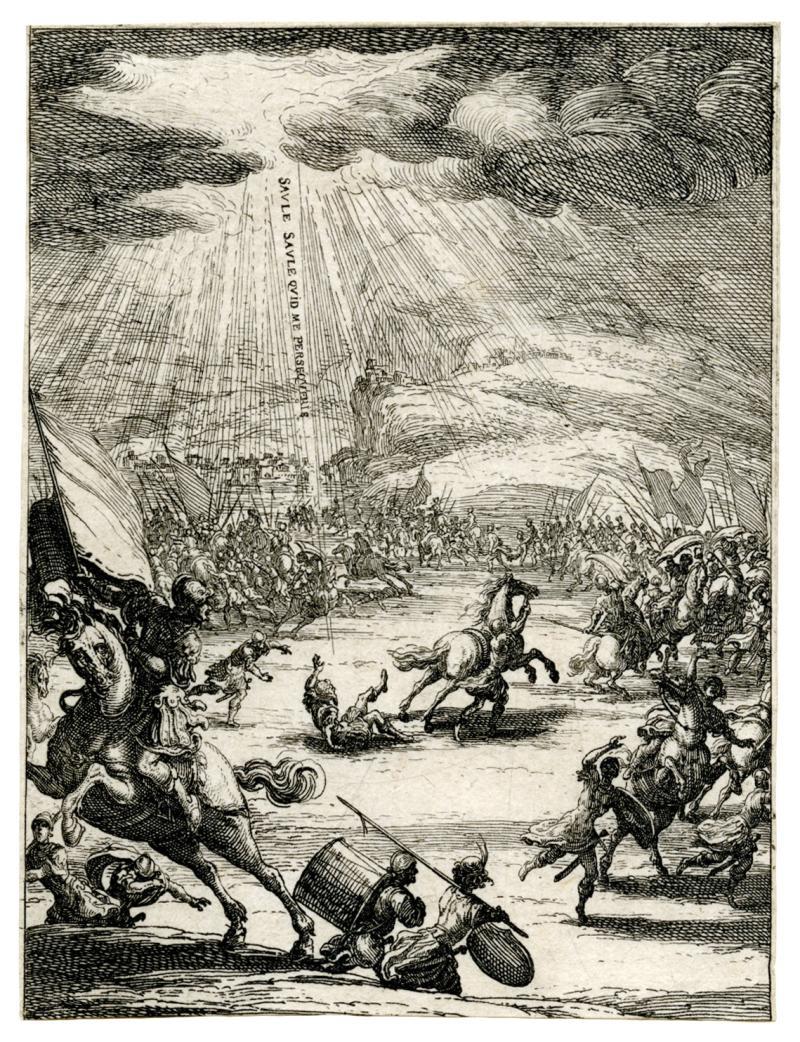

The Conversion of St. Paul

after 1621, before 1629

Etching; published by Israël Henriet (French, ca. 1590–1661)

States i/iii; Lieure 676; Meaume 97

Trimmed to Plate mark on three sides; lower margin trimmed

Jacques Callot was born into a family that served the Duke of Lorraine Court in Nancy, and his parents hoped he would rise in the ranks of courtly life. But, Callot pleaded with his parents to let him pursue a career in the arts. Discouraged by their lack of encouragement, he ran away to Rome and apprenticed himself to Philippe Thomassin (1562-1622), who was an ex-patriot French publisher and engraver. In 1612, Callot became a draftsperson and printmaker to the Medici Court in Florence but returned to Nancy after his patron’s death in 1621. In Nancy, his reputation as an etcher inspired many commissions. He continued making drawings and etchings, specializing in subjects of court life as well as gritty, city subjects of gypsies, clowns, and beggars. He also etched many military and religious subjects. In his lifetime, Callot made more than 1,400 etchings and his works were highly desired by collectors throughout Europe. Notably, Rembrandt and Goya collected and were influenced by Callot’s etchings.

Callot made two significant improvements to etching, which transformed the intaglio printing technique. The first was his experimentation with the recipe for ground, which usually was wax-based and somewhat unstable in the acid bath. Callot tested grounds mixed with the varnish used by lute makers, finding that durability of varnish-based coatings allowed for a deeper biting. He also perfected stopping-out the ground so that he could reintroduce the plate into the acid bath multiple times, achieving subtle gradations of lines from soft to dark and rich. Callot also invented a new tool called the échoppe, which had an angled, oval-shaped ending replacing the sharp needle used in traditional etchings. By turning the échoppe, Callot could vary his contours from fine, light lines to thick, “swelled” lines that provided depth and definition.

Conversion of St. Paul, likely made soon after Callot’s return to Nancy, is a good example of the new etching techniques that allowed Callot to create highly detailed etchings. The composition is sweeping and panoramic, yet the print is small -- only about 4 by 2 ½ inches. Callot’s ability to give the impression of monumentality with such small figures results from the detailed precision of his lines. The subject of Paul’s conversion was one that Callot depicted several times. The story is recorded in Acts, chapter 9. As a Jewish zealot, Saul was trying to eliminate devotees of the new religion of Christianity. He traveled by horseback to the city of Damascus to arrest Christians, but just outside the city, Saul and his men were suddenly exposed to a bright light, so powerful that it knocked Saul to the ground. A voice came from the sky: Saul, Saul, why do you persecute Me… I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting.* The churning drama of Callot’s composition underscores the spectacle of Saul’s conversion. The etching divides land from sky about halfway with a lightly etched city view on the horizon. The figures surrounding Saul’s vision swirl around him in confusion. Adding to the theatricality are rearing horses, wind-blown banners, sprinting soldiers, and dark clouds broken by the luminosity of God’s presence. Rays of diagonal light descend from the heavens with a central banner of light inscribed with the words: “SAVLE SAVLE QVID ME PERSEQVERIS."

-JL

*Acts 9:4-5 (NIV).