Westmont Magazine Augustine’s Aspirational Imperfectionism: What Should We Hope for from Politics?

By Jesse Covington, Director, Augustinian Scholars Program and Associate Professor of Political Science

LOOKING AT THE GLASS

Is the glass half empty or half full? Does your answer reveal something about your disposition and outlook? Interpreting responses to this question may not be so simple. My father explained to me at an early age that answering “half empty” reflects true optimism because it assumes the normal status of the glass is full. The “half-full” folks, he told me, begin from the bleak starting point of an empty glass.

In politics, we often think of liberals as optimists and conservatives as pessimists. Liberals can be ever-hopeful, aiming to improve society through government efforts to help communities enjoy greater justice, equality, freedom, health care, security, prosperity, etc. In contrast, conservatives can be wary of state powers to make things better, counseling a politics of restraint and limits instead. As Lord Salisbury (Robert Cecil) reportedly said, “Whatever happens will be for the worse, and it is therefore in our interest that as little should happen as possible.” In light of my father’s wisdom, we might say that political conservatives are optimistic about the present and pessimistic about the future, and political liberals are pessimistic about the present and optimistic about the future.

How can we relate such assessments of secular history to redemptive history? The Bible’s story of God’s work in the world clearly affirms aspects of both the liberal and conservative visions: the present involves both created good and fallen distortion. The future includes a call for humans to act redemptively but with expectations tempered by the persistent impact of the Fall until Christ returns. The eschatological tension of “already-but-not-yet” accounts for goodness from the creation in its treatment of the “already.”

Unsurprisingly, Christians tend to lean one way or the other. We emphasize either the goodness of creation or the fallen condition in our political outlooks, although we can configure this in several ways relative to the present and the future. On the one hand, a significant number of Christians frame a more liberal or progressive political outlook in biblical terms, perceiving a good deal of suffering and injustice in the present and casting a hopeful vision for a corrective politics that can act as a force for good. In redemptive-historical terms, this vision sees politics as an important instrument for rescuing the creation from the present effects of the Fall. On the other hand, some Christians cast a bleaker outlook for the sort of future politics can provide, seeing human sin as the central problem to be controlled—both in rulers and the ruled—and counseling a politics of restraint. In redemptive-historical terms, they emphasize preserving what limited goods are available now (things could always get worse!) and delayed ultimate fulfillment.

Both visions include important truths about a biblical outlook for political life. Creation is good, Christians are called to work redemptively to alleviate suffering and injustice, the impact of the Fall is lasting in this “time between the times,” and power is always dangerous. How then can we shape our political paths?

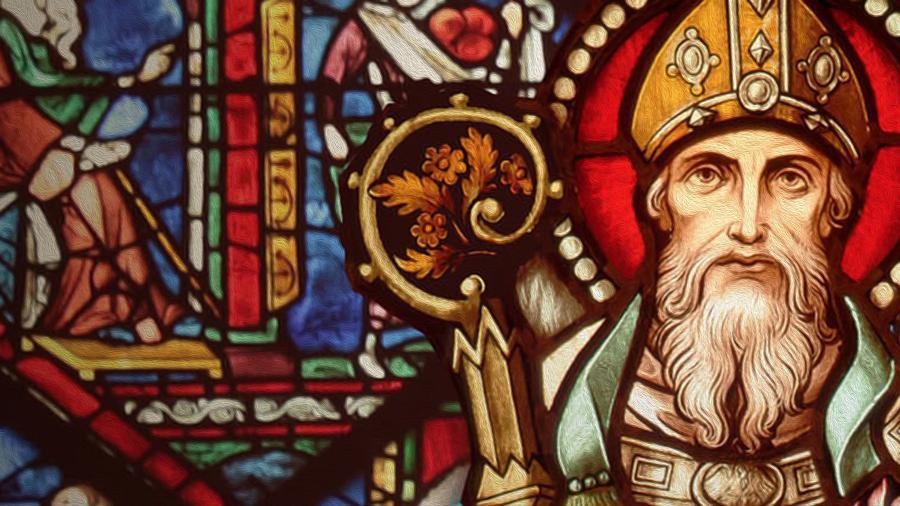

St. Augustine, whose magisterial “City of God” explores the relation of redemptive history to secular history, helps us address this question with an outlook I describe as “aspirational imperfectionism.” More a third way than a middle way, this approach is deeply shaped by enduring tensions that resist collapsing in either direction. In a time of political polarization and overstated political promises on all sides, we do well to embrace such tensions and reflectively explore third ways. While I focus here on applications to politics, Augustine’s vision carries important implications that extend well beyond to other areas of society.

AUGUSTINE AND POLITICS

Modern readers of Augustine often see his political vision in fundamentally pessimistic terms. Reinhold Niebuhr’s political realism drew heavily from Augustine’s thought (see his essay, “Augustine’s Political Realism,” for example). Indeed, Edward Portis gives a chapter on Augustine the deeply pessimistic title: “The Politics of Sin.” This rather gloomy reading holds some truth: Augustine takes sin seriously and accounts for it in his politics. But this account is incomplete. Augustine embraces the goodness of creation—a feature that sets him apart from the Platonists with whom he is sometimes grouped. In particular, he believes in the goodness of human embodiment and affections and a deeply hopeful eschatological future. How he relates the goodness of creation, fallen reality, and anticipated redemption provides an instructive template for cultural engagement that transcends the dichotomies of standard approaches.

On the one hand, Augustine’s vision is deeply aspirational. Although he believes that the highest human good is in heaven, Augustine expresses a rich appreciation for earthly goods and their contribution to human flourishing. While some think first of Augustine’s early articulation of just war theory, his political thought focuses on the pursuit of earthly peace. Echoing Jeremiah 29, Augustine exhorts Christians, like Israel in its Babylonian captivity, to seek and defend the earthly peace that politics provides—even when controlled by a still largely pagan Roman empire. What exactly does this earthly peace entail? Augustine describes it in terms of temporal goods: “the peace that consists in bodily health and soundness, and in fellowship with one’s kind; and everything necessary to safeguard or recover this peace—those things, for example, which are appropriate and accessible to our senses: light, speech, air to breathe, water to drink, and whatever is suitable for the adornment of the person” (City of God XIX:13). His aspirations for politics reflect a fundamental affirmation of creation’s goodness and the importance of ordering things rightly. This includes the objective goodness of the material world but also to truth accessible to human knowledge and a common moral order. All humans, Augustine says, can aspire to know more about reality, to act increasingly in accord with the virtues, and to profitably engage with the goodness of material creation. His aspirations for politics reflect these shared dimensions of the created order and largely align with later Christian emphases on the “common good.” Contrary to some contemporary accounts, Augustine’s politics assumes both significant commonality and aspiration for improvement in shared goods. In an important sense—and contrary to many interpreters—he offers a hopeful vision of politics as striving for greater justice and the conditions of human flourishing.

Contrary to accounts that paint him as solely a pessimist or a conservative, Augustine adamantly believes that the goodness of creation cannot be obliterated. He says that political communities—what he calls “commonwealths”—can be better or worse. When a people’s “shared objects of love” are better, the commonwealth is better. When shared objects of love are worse, the commonwealth suffers (City of God, XIX: 21). Augustine’s exhortations for Christians to seek earthly peace encourages striving for political improvement with an expectation of achieving real, objective goods—both material and moral. Clearly, Augustine’s vision for politics extends far beyond only restraining sin and making life bearable while awaiting eternity. The foundation of Augustine’s politics aims at greater earthly peace: the common created good that makes human flourishing possible.

Nevertheless, Augustine is no optimistic progressive. He does not think that such improvement is inevitable or that ultimate success is attainable inside of time. His political vision remains one of limits and imperfection. His paradigm of two cities, defined by their loves, is especially pointed here, particularly as his understanding of redemptive history relates to secular history—politics inside of time. The City of God—composed of those who love God—stands in marked contrast to the terrestrial city—composed of those who love themselves. Augustine has no expectation that politics can overcome the gap between the two, as they have divergent final ends. Instead, he casts politics as brokering a limited peace between them, focused on the creational goods of earthly peace. The irreducible division between the two cities leads Augustine to reject Cicero’s account of the political commonwealth as too perfectionist. Where Cicero focuses on a “shared sense of right,” Augustine insists that divergent teloi (purposes) of the two cities render this impossible: true right requires true justice, which must include rendering to God his due (City of God XIX: 21). Thus, political justice and the goods of earthly peace must always be proximate rather than final.

It is here, amidst the proximate good of politics, that we encounter Augustine’s well-known account of coercion. Sin makes coercion necessary for human communities to live in peace, but the justice of such coercion is always imperfect. Even a just judge cannot know guilt with certainty and always runs the risk of violating justice amidst efforts to do justice. Augustine says the wise ruler will still do his duty and rule but insists he can’t be truly happy given the miseries associated with finitude and sin (City of God, XIX: 6). In short, the eschatological tension of our location in redemptive history tempers what we can expect of political goods. Sin must be restrained but can’t be eradicated. We can pursue political justice, but it will remain imperfect. Even “good” commonwealths will never (inside of time) agree on a sense of right in terms of theological justice. Thus, while fundamentally aspirational, Augustine’s politics reflects the “not yet” of the eschatological moment. Overpromising political visions—of both fulfillment and restraint—cannot help but participate in pagan idolatries.

APPLIED AND EXPANDED

So what does aspirational imperfectionism look like in practice? My experience years ago as a distance runner at my university provides an analogy. Even though I knew I would never be great, I trained rigorously. I aspired to improve in terms of real, objective criteria (faster times), despite knowing my best efforts wouldn’t make me an elite college athlete. I had to plan and execute in light of attainable goals: I couldn’t run the first mile of a five-mile race at a record-breaking pace, or I’d never finish. But I still ran—and improved.

Like my experience as a runner, an aspirational imperfectionism in politics seeks real improvement in terms of earthly peace but with tempered expectations. What undergirds this sort of approach? While I’m sure this list could be expanded, I suspect that humility (a prominent virtue for Augustine) about our knowledge, goodness, and abilities plays a key role. Likewise, prudence—and with it a commitment to incremental change, accountable power, a suspicion of perfectionism, and compromise (an oft-neglected feature of Augustine’s political thought)—seems vital. Moreover, a certain detachment from outcomes (implicit in ethical commitments that take means seriously) is essential.

Humility, prudence, and detachment are all well and good, but there must be something toward which one aspires. These qualifiers require a telos, a purpose. Thus, despite the discomforts of making such claims in increasingly relativistic contexts, conviction about the good and a commitment to seeking that good for others are indispensable to the “aspirational” side of the equation. Rooted in a creational theology and motivated by a redemptive vision, “earthly peace” must have content in terms of real goods, both material and moral—content that helps to secure the conditions in which human flourishing is possible.

Of course, these concepts have broader applications than politics. Aspirational imperfectionism is why, as a father helping my child with schoolwork, I may accept the long-embattled essay as “good enough” rather than forcing my relationally weary son to do it again, even though I know he is capable of better. There’s a real standard that we’re chasing, but more than one good is at stake. Forcing the issue may do more harm than good; there’s always next time. It is why my wife, whose graduate training included biblical counseling, periodically reminds me that a Christian should never be shocked by sin, even when grave. Grieved? Yes, but never shocked. This refusal proceeds from an honest assessment of the time in which we live—the time between the times—and the realities that shape it. It offers no concession to sin, no acceptance of its place in human behavior. The grief is real and is fully compatible to an earnest striving after holiness. But it’s also compatible with prudent safeguards against any anticipated recurrence. Many related applications might be fruitfully explored.

In short, Augustine points us to political faithfulness in light of the full scope of redemptive history. Our hopes for politics include pursuing real goods (could love of neighbor counsel anything less?), but with the recognition that these goods remain tempered, limited, and proximate inside of time. We might describe this as the drive of liberals and the expectations of conservatives. For Augustine it is captured by the image of the pilgrim or sojourner who invests deeply in his current context, but without mistaking it for home.

A version of this article originally appeared in Public Justice Review, a publication of the Center for Public Justice.