Westmont Magazine Modeling a Leadership Program on the Life of Augustine

by President Gayle D. Beebe

“For the human race is at once social by nature and quarrelsome by perversion…this is why…the earthly city glories in itself…while the heavenly city glories in the Lord.”

St. Augustine, “The City of God”

In 410 AD, Alaric and the Goths stormed the citadel of Rome and burned the city gates, symbolic of conquest in the ancient world. The act traumatized the citizens of Rome and set off a wave of panic across the entire empire. Eventually, the Romans repelled the barbarian hordes, and the political leaders regrouped. But like all corrupt politicians, they needed someone or something to blame to divert attention from their own gross incompetence. As historians have carefully documented, the Romans landed on the Christians as the cause of their demise and began to mount a case against the new religion.

Meanwhile, living across the Mediterranean Sea in his native North Africa, Augustine heard of the initial attack, the attempted conquest and the sad response. Appalled by the thought that Roman leaders might mount an acceptable case against the Church, he began to write “The City of God.” From 413 to 426 A.D., he excavated the history of the Roman Empire, pointing out in case after case that, contrary to popular belief, the Christians had not caused the demise of Rome. Instead, he identified them as the moral thread holding the empire together.

Augustine died four years after writing this last book, his magnum opus in which he makes the finest defense ever for the critical importance of producing thoughtful Christian leaders in every generation of every society. Augustine is such a magnificent example of what we want for every Westmont graduate: a capacity to engage every sphere of society with skill, savvy and competence while making an able defense for the love and hope they possess through Jesus Christ.

By education and guided experience, we want every Westmonter to prepare for a life of significance by engaging the full range of our robust education. Through the combination of classes and co-curricular activities, we seek to produce generation upon generation of bright, capable graduates imbued with the spirit of Augustine.

Augustine helps us understand how to make sense of our life and God’s greater purposes in and through it. He teaches us how to think correctly about the known things of the universe so we can understand the greater mysteries of God. Augustine recognized that we are both great and wretched, that we possess incredible capacities to do enormous good but also battle internal conflicts that often lead us astray. He understood that Christians would only win the right to advance their view of reality and their response to it if they could outthink the pagan opposition, prove to be better citizens and fundamentally advance the spiritual, intellectual and cultural fortunes of their civilization. He advocated that Christians embrace the known evidence of their contemporary world so that non-believers would find them credible on things they knew to be true so that they could then speak of the things of God that remained hidden. He had the initial capacity and eventually the spiritual maturity to make the pivotal response that gave Christianity a fresh impulse of momentum propelling it through the rest of the first millennium. Ultimately, the spirit of love best exemplified by Augustine is captured in another penetrating quote from The City of God, “…what does love look like? It has the hands to help others. It has the feet to hasten to the poor and needy. It has eyes to see misery and want. It has the ears to hear the sighs and sorrows of others. That is what love looks like.”

More than 25 years ago, Robert Greenleaf described the leadership crisis in America as unprecedented. He defended his perspective by cataloguing the collapse of moral and ethical leadership on virtually every front. But think what has happened in the intervening time. If anything, the situation has only worsened. On virtually every front, we see the collapse of moral and ethical values and a loss of support for faith-based solutions. Increasingly, conversations with thoughtful people eventually highlight the growing ambivalence about Christianity and the belief that Christians are part of the problem, echoing the criticism of Christians during Augustine’s life. Our goal as an educational institution is to pursue the twin rails of our mission: rigorous academics and deep love for God and in the process prepare our graduates to lead and serve in every sphere of society, just as Augustine exemplified and encouraged so many hundreds of years ago.

We want our Augustinian students to become great thinkers with hearts committed to God. In other words, we seek to develop them into a certain kind of person and to help them grow both intellectually and morally. But we also work to equip them with specific leadership skills so they can apply their understanding and their faith in addressing the great and pressing issues of our time. We want them to become known as leaders dedicated to things greater than themselves who can build institutions, organizations, businesses and communities that endure and reflect our highest ideals. In this way, they can demonstrate the power of God and the valuable contribution Christians can make in creating a just and flourishing society.

In the “Confessions,” Augustine documents the personal journey to God. In “City of God,” he describes how to build a functioning society. While we must attend to our own spiritual growth and formation, we must also move beyond a focus on ourselves and seek to discover how God can use us to carry out his work—and share his grace, mercy and forgiveness—in an increasingly troubled society. We’re praying that our graduates can bring this kind of transformative leadership to every sphere of society throughout the world.

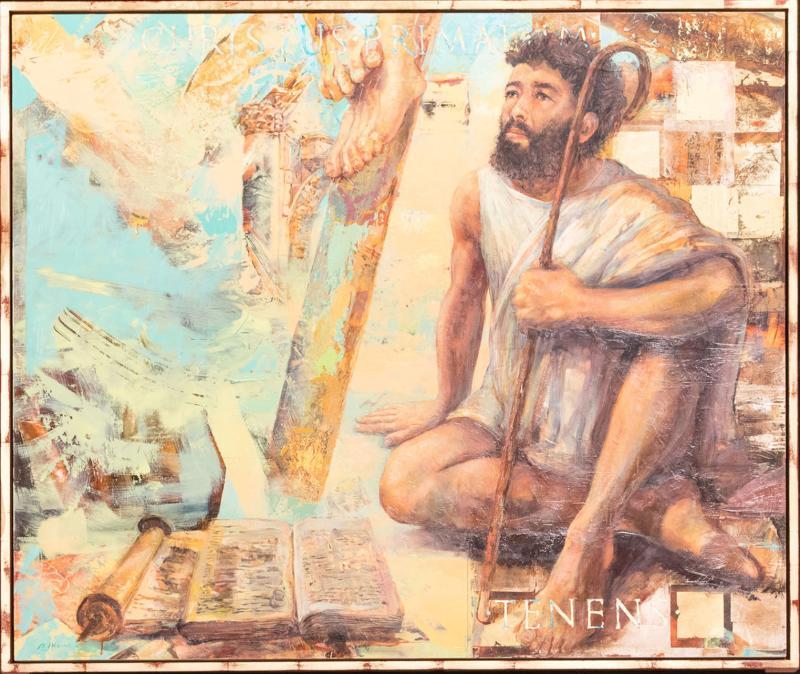

This painting of Augustine by Bruce Herman was commissioned by President Beebe in 2017.

Leading by Vulnerability Through Prayer

by Karis Cho ’21, Augustinian Scholar

Funnily enough, I learned how to pray—body, mind, and heart—from the professors in the Augustinian Scholars program that I’ve been lucky enough to get to know.

I remember watching Dr. Jesse Covington pray with his hands open, sitting in a posture to receive, in my first-year seminar. The emphasis that he put on how we are embodied beings means that I always pray with my hands open to receive now. This practice is a powerful way that I open myself, through my body, to the presence of the Holy Spirit, even when I struggle to open my mind or heart. During quarantine, as I missed the gift of placing my body in the presence of others—of walking to and from class, of hugging my friends hello and goodbye, of sharing a meal with someone—I found myself unable to do anything but fall to my knees and pray.

In my sophomore year, Dr. Telford Work taught me how to avoid committing heresies, which is a surprisingly difficult task to do. But he also taught me, during my junior year seminar with him, how to take prayer back to the biblically, theologically sound basics. He assigned a reading from Vincent Donovan’s “Christianity Rediscovered” about how the most dangerous, most powerful prayer is praying that God’s continuing, creating work would be done in and through me, rather than somewhere out there, somewhere removed from me.

During this year, I’ve had the privilege of basking in Dr. Sarah Skripsky’s radically loving presence in my senior capstone class. She has demonstrated for me what it means to have a soft heart while praying audacious prayers. Dr. Skripsky stands as my example of obedience to God, which seems simple but proves to be very difficult, and living into God’s will for a full life and full justice for everyone. At the beginning of every class, she asks one of us to lead an opening devotional of our choice, which has given me an opportunity to lead with vulnerability through prayer.

Cultivating Stewardship

by Caleb Marll ’22, Augustinian Scholar

One of the key elements of the Augustinian program is stewardship. Many students come to Westmont already equipped with great minds and hearts for God, but it’s not simply about having these gifts; it’s about using them to love God and love others well. I remember discussing the Parable of the Talents from Matthew 25 and realizing that we aren’t called to set our God-given gifts as trophies on a shelf, but rather to invest them in the Kingdom. By taking an interdisciplinary approach to Scripture and the writings of early Church leaders and saints, the program has taught me how to faithfully cultivate my own mind and heart for a deeper relationship with the Lord.

An Augustinian Scholar also learns how to lead with truth and humility. As the apostle Paul writes in 1 Corinthians 10, “Whatever you do, do it all for the glory of God… For I am not seeking my own good but the good of many, so that they may be saved.” Part of the Augustinian education is learning how to live faithfully in the world’s societies and institutions while also bearing witness to the coming Kingdom. The rich curriculum of the program demonstrates that we aren’t called to seek the fame and riches of the world, but rather to live and lead as disciples and servants.

Each year, Westmont invites nearly 300 candidates to compete for the Augustinian Scholars Program.

For more information, please visit westmont.edu/augustinian