Westmont Magazine

By Deborah Dunn, Professor of Communication Studies and CoDirector of the Westmont Initiative for Public Dialogue and Deliberation

(Editor’s note: This opinion piece appeared in the Santa Barbara Independent newspaper.)

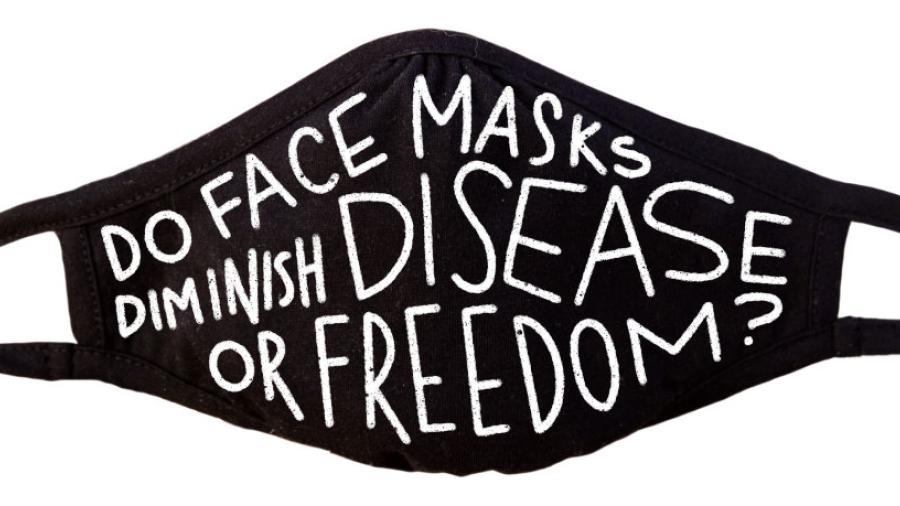

One of the more “interesting” aspects of living through this pandemic is the judgment, indignation, and even rage on display over the wearing of face masks, physical distancing, and shelter-in-place orders. We see these displays online, in protests, and, tragically, in violent outbursts. For some of us, our blood boils when we see non-masked, non-distanced folks at bars and on beaches having the party of their lives—yet for others of us, we are incensed that an employee might refuse service or entry if we’re not masked, or that a government official would order us to stay home. We know some folks who are afraid to leave their homes, but we know other folks who think this is all media hype. And practically speaking, most of us wonder if anyone in charge really knows how best to navigate these troubling times.

When I help community members identify what they hold valuable, I borrow an exercise from Martín Carcasson of the Colorado Center for Public Deliberation. I ask folks to rank a list of values, recognizing that they might consider all of them important. But they must choose the most important and the least important. Sometimes we focus on the values that are built into the U.S. Constitution. Sometimes I give them nine values to rank. No matter whether they are ordering five values or nine values, individuals vary in their responses. Some might rank safety or security as most important, while others rank freedom as most important. Some might rank justice highest and equality lowest. Depending on time, either we discuss what we hold valuable and how we order them, or sometimes we just have a show of hands.

I always notice the surprise when people realize they rank these things differently from their friends and neighbors. When facilitating community conversations, a key component comes from the Kettering Foundation and National Issues Forum model of deliberation: helping participants notice how their positions and perspectives on issues ranging from immigration to what to do about the opioid epidemic are informed by what they hold valuable. It’s also critical that they recognize that most everyone in the discussion also values freedom, but they may think that equality comes before freedom, or that without safety, no one is free. This helps us re-humanize those we disagree with and moves us toward a productive deliberation wherein we examine the tensions and trade-offs inherent in potential actions, policies, or programs under discussion.

I think with COVID-19 we don’t have to look very far to identify those values and tensions and trade-offs. It’s easy to see that some of us value our safety and security more than we value our freedom (albeit temporarily). Or, we value the safety and security of the most vulnerable members of the population over our own freedom to shop or dine as we please. It’s not that we think freedom is unimportant. It’s that we think that our freedom won’t do us much good if we’re dead. Yet others of us worry that even the temporary erosion of our civil liberties will be a slippery slope toward less and less freedom, which will become more and more permanent. If we only focus on safety OR freedom, we end up at an impasse—or the rage we see playing out. Health care professionals beg us to wear masks not so much to protect our own health, but to protect the health of the most vulnerable. By reducing the virus spread by non-symptomatic carriers, we protect the health of others. Yet most debates on mask-wearing in the public square focus on whether or not the mask wearer will be protected. The data showing that a mask won’t protect you from getting COVID-19 are trotted out, and a healthy person (often a young, healthy person) determines not to wear a mask. What if we could change the conversation to include the other things we hold valuable, expanding the range from simply freedom vs. safety to include community and justice and individual responsibility?

We’re lacking more sophisticated conversations about how we manage the built-in tensions when it comes to weighing the things we hold valuable, both for ourselves and for others. Most debates about masks still boil down to whether or not people feel personally vulnerable to the virus and whether or not they feel that personal rights are being violated.

“Most debates about masks still boil down to whether or not people feel personally vulnerable to the virus and whether or not they feel that personal rights are being violated.”

In addition to these tensions, we see how fear makes it even more complicated. For some, the scariest threat is getting sick or having a loved one get very sick or even die. But for others, the scarier threat is losing a source of income and therefore the ability to maintain a roof overhead and food on the table. When we’re afraid, we can sometimes act selfishly, irrationally, or foolishly. Two friends recommended I read Atul Gawande’s book “Being Mortal” just before the pandemic hit. I read it because I’m living with the reality that I won’t have my father much longer. One of Gawande’s key themes is that the medical profession may help us literally live longer, but it may not help us live the lives we want to live.

In this pandemic, I see the tension between Fighting for Longer Life vs. Fighting for What Makes Life Meaningful. The elderly in nursing homes are particularly vulnerable (as are people in prison or other institutionalized settings). In many cases, reaction to safeguard patients results in prohibiting visitors and even being confined to their rooms.

Yet we know that loneliness and solitary confinement have dire physical and emotional consequences. So, in order to protect our most vulnerable, we separate them, but this cure is potentially more painful than the disease. For families with young children, several months without seeing a grandparent can mean the difference between a child remembering that grandparent or not. How can we not be disturbed by the images in the news of a nurse trying to help a family FaceTime with a loved one dying in hospital, mostly alone? It’s heartbreaking.

We’re lacking the hard conversation that weigh these tensions and tradeoffs. When we weigh civil liberties and freedoms with the need for safety and security. When we weigh the needs of the many vs. the needs of the few. When we weigh preserving human life via non-illness vs. preserving human life via wellness in all senses of the word. We need to have explicit conversations about how we might manage the risk to our most vulnerable but without taking from these very individuals any quality of life, any sense of being part of a human community. We have to acknowledge that we are social beings. We need human company and human touch. So how can we figure out strategies that allow us to be human?

“Once you train yourself to look for how the values you choose inform our perspectives and positions, you recognize that it’s not about shouting the other party down. It’s about engaging the other party to work through those tensions and tradeoffs so we can actually make good decisions and good policy, whether for our country or ourselves.”

As we muddle our way through this pandemic, we have also become very aware of the fault lines in our society between those who have power and resources and those who don’t. A middle-class person with a job that can be done remotely has many more choices when it comes to deciding how to comply or resist health orders. So many of the essential workers are also the poorest and therefore have much less freedom or flexibility to decide whether or not it is safe to work. They must work if they want to live. They must work in sometimes unhealthy conditions and risk contracting the virus themselves or passing it on to their loved ones. If they speak up, they may be fired or sidelined. So they don’t speak up. There is a reason why, in many societies, from the USA to Brazil, we see that infection, hospitalization, and death rates are higher in poor communities or minority communities. This is not an accident.

As David Brooks has noted, “inequality makes us less resilient.” We are connected—so we have to connect our responses. In this era of populism, nationalism, and me-first, we cannot act well as a larger, global community. The individuality of states, counties, and local governments in an era of global webs of connection may not make as much sense as they would have even decades ago.

Despite these challenges, we see signs of hope and signs that people are making the best decisions they can. There are countless stories of people being helpful, even sacrificial, running errands, shopping for others, helping neighbors, checking in, and so on. In California, we suddenly found beds for people living without homes, whether motel rooms or properly distanced shelter beds. And we provided hand-washing and cleaning stations. Of course, it took a pandemic to get us to act, but we showed ourselves that we can do something. Where there is public and political will, there is a way!

In spite of the very tragic killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, I’m encouraged by the number of people who have taken to the streets. These people still care about justice and human rights, and they are willing to sacrifice their own safety for the safety of others. Though in these demonstrations, we see even more hard choices playing out: to preserve our own safety and the safety of those we love; or to march, thereby risking spreading and contracting the virus; or not to march, thereby risking that unjust violence ravages our families and communities in other ways.

Once you train yourself to look for how the values you choose inform our perspectives and positions, you recognize that it’s not about shouting the other party down. It’s about engaging the other party to work through those tensions and trade-offs so we can actually make good decisions and good policy, whether for our country or ourselves. We don’t need a debate in which we vote for the winner or who

represents our own values best. We need better ways of talking and listening together to figure out the solutions. Put the economists, the health experts, the social workers, and the poets in the same room. Hash out the upsides and the downsides of all the proposals. Weigh the trade-offs. Acknowledge that we can’t solve every problem. Be transparent about it. Allow citizens to hear the deliberation or read the transcripts. Help the entire electorate walk through this process. The outcome will be so much better than shooting the store employee because he asks you to put on a mask.