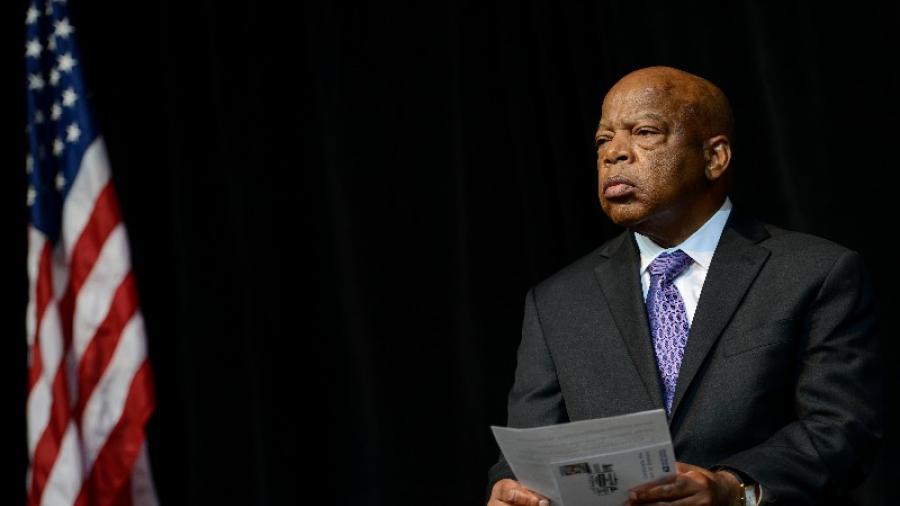

Westmont Magazine The Honorable John Robert Lewis

A Statesman, Civil Rights Leader, and One Who Walked with the Wind

by Marcus “Goodie” Goodloe, new Westmont parent and Senior Fellow for Ethics and Justiceat Dallas Baptist University’s Institute for Global Engagement

In the Scriptures, the writer James (one of the important leaders of the early church), informs us that “life is but a vapor.” We appear for a little while, and then we vanish (James 4:14).

In a dramatic yet poetic sense, this passage speaks to the brevity of life and its fragility that embraces us all daily with God’s unmerited grace. James’ words also serve as a clarion call for each of us to consider what we say, what we do, how we give, and how we serve others between the beginning of our lives and the end of our days. I call it being mindful of the “dash,” the line that separates your birthdate and death date.

During the time given to him, John Lewis gave immeasurably. He did for others what they could not do for themselves, he spoke with moral clarity on the things that matter most, and his entire life became a force for good. He was mindful of the dash.

Born February 21, 1940, a son of sharecroppers in the segregated south, Lewis spent his youth preaching to chickens. In his words, he had a captive audience as he took to his daily chores, and he figured the practice he got could be a benefit to him and a blessing to the chickens who’d yet to be redeemed. Lewis had a keen and profound sense early on that he had a message to speak. By all accounts, his life spoke profoundly.

He enrolled in American Baptist College in Nashville, Tennessee, with the hope of transferring to Troy State in Troy, Alabama. He submitted his application but never received an acceptance letter nor a letter of denial from Troy. In 1957, Lewis wrote to Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., of his interest in the struggle for civil rights and of his dilemma in waiting to hear back from Troy State. King responded and invited the young Lewis to meet with him in person to discuss his undetermined future. The civil rights leader sent a roundtrip bus ticket, and Lewis traveled to Montgomery, Alabama, to meet King. When Dr. King laid eyes on Lewis, he referred to him as “the boy from Troy.” Lewis eventually completed his studies at American Baptist College and later earned a Bachelor of Arts in philosophy and religion from Fisk University.

Lewis went on to found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and was the youngest speaker on the program at the historic March on Washington, August 28, 1963. Prior to that, at the age of 21, he was one of the founders of the Freedom Riders, a group dedicated to desegregating buses across state lines. During a Freedom Ride in Rock Hill, South Carolina, in 1961, Lewis was attacked and beaten over the head by Elwin Wilson, a Ku Klux Klan supporter. In 2009, Lewis responded to an apology from Wilson by extending his forgiveness. Arrested more than 40 times, Lewis did not shrink back from direct nonviolent peaceful protest. He practiced the ethics of love and peace as modeled in the lives of Jesus, Mahatma Gandhi, and King.

During the march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in March 1965, Lewis was nearly killed at the hands of state troopers. He was clubbed and beaten, resulting in a loss of consciousness due to a fractured skull; a steel plate was inserted in Lewis’ head along with dozens of stitches. He often said in reference to that day on the Pettus bridge, “I gave a lot of sweat, some blood, while others gave their lives.”

Years later, in 1986, Lewis was elected to the U.S. Congress as the representative for Georgia’s 5th Congressional District. He was unyielding in his pursuit of justice and equality for others and became a stalwart champion of finding common ground with people who opposed him.

John Lewis’ memoir, “Walking with the Wind,” tells the story of his humble beginnings and his lifelong dedication to public service, which he loved so dearly. His sacrifice for what King called the “beloved community” was heard around the world. In 1991, when South Africa’s Nelson Mandela was freed from prison after 27 years in jail, he traveled to the United States on a goodwill tour to thank those who had supported the mission to end the racist policies and structures known as apartheid. Mandela recognized Lewis at their initial greeting and spoke with heartfelt appreciation of how Lewis had been a great influence not only on his own life but also on the cause to confront racism and injustice on that continent.

At the passing of Lewis, French President Emmanuel Macron said, “So much progress has been made because of him. John Lewis was a hero.” Award-winning scholar and presidential historian Douglas Brinkley called Lewis the “Mahatma Gandhi of America.”

He was unyielding

in his pursuit of

justice and equality

for others and

became a stalwart

champion of

finding common

ground with people

who opposed him.

On February 15, 2011, Lewis was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Upon bestowing the award, President Barack H. Obama said in part, “Generations from now, when parents teach their children what is meant by courage, the story of John Lewis will come to mind, an American who knew that change could not wait for some other person for some other time, whose life is a lesson in the fierce urgency of now."

In 2015, Lewis collaborated with Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell for a graphic novel to tell the story of the Civil Rights Movement. This award-winning trilogy was simply titled: “March I,” “March II,” and “March III.” But there was nothing simple about its contents. It tells the firsthand account of Lewis’ lifelong quest to make good on the mission “to redeem the soul of America.”

I never met John Lewis, but I did have the honor to speak with him by phone in 2010 as part of my research on the life and leadership of Martin Luther King Jr. and his work with athletes and entertainers during the civil rights movement. Lewis was kind, forthright, thoughtful, and encouraging. I was nervous for a host of reasons but mainly because I realized I was engaged in a conversation, although brief, with a man who altered the course of human history in ways that are simply immeasurable. The first week of July of this year, amidst COVID-19, I sent a group text to my family and called for a mandatory family film night. The documentary “John Lewis: Good Trouble” was being released that week, and I wanted my family to experience what I knew would be an informative blessing to our minds, bodies, and souls. This was certainly the case and so much more.

Lewis was a husband, father, grandfather, mentor, and friend to many. My heart is heavy with his passing. The breadth and depth of his life’s work cannot be overstated. He embodied the best of America’s ideals; there will be much ground to cover in the telling of his life story and the legacy he leaves behind. Lewis walked and traveled to the edges of this earth and through some of the darkest valleys and deepest depths of America’s soul, a soul mired by a complicated history of both greatness, yet injustice; of right, and yet wrong; of truths, and yet lies.

In his 80 years on this earth, Lewis sought to do right in the face of wrong, confront hubris with humility, rebuke hate with love, and combat fear with faith. He was constantly on the lookout for what he called “good trouble”: his unyielding commitment to comfort the wronged and confront those who did wrong. Lewis was a follower of the teachings of Jesus, and he remained in a posture of teachability and service and devoted his life to the Scriptures.

My sincere condolences to the entire Lewis family, and his friends, and colleagues. I thank God for giving this world a man who “walked with the wind” and forged a path that those who aspire to “redeem the soul of America” can follow. Rest in peace and power, the Honorable John Robert Lewis. Say hello to a man named King. I look forward to meeting you both on the other side.

Marcus “Goodie” Goodloe, Ph.D. travels around the country mentoring students and educators, business professionals, athletes and entertainers, and faith communities on a range of issues, including cultural and interpersonal relationships, leadership, team and synergy, character formation and faith. He serves as an adjunct professor in the Gary Cook School of Leadership at DBU and speaks frequently for the Veritas Lecture Series. He specializes in leadership through influence, social justice, and research regarding the life of Martin Luther King Jr. He wrote “KingMaker: Applying Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Leadership Lessons in Working with Athletes and Entertainers” (2015), and co-wrote “Habits: Six Steps to the Art of Influence” (2017). His daughter, Hannah ’24, attends Westmont.

President Beebe remarks of Goodloe: “I’ve so appreciated the opportunity to learn from Dr. Goodloe, one of the leading MLK, Jr. scholars in the nation. The life and legacy of John Lewis has ignited a level of new interest in the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Goodie’s work is helping pave the way. Of course, I’m especially

thankful for his role as a Westmont parent!”

Photography of Goodloe by Heather Leven Photography