Westmont Magazine How My Westmont Education Led Me To Lifestyle Medicine

by Sara Johnson ’05, MD, MPH

I began my medical career practicing emergency medicine at Los Angeles County + USC Medical Center (LA County), one of the busiest trauma centers in the country. We called it the Knife and Gun Club — the military sent medics to train there because it represented the closest approximation to warfare on U.S. soil. One pivotal patient encounter there involved nothing so violent, yet it was equally devastating and far more common: a cardiac arrest.

An active fire chief in his late 40s collapsed while working out in the gym at his own fire station. He’s in cardiac arrest and surrounded by 15 paramedics who begin immediate resuscitation and transport him to our Level 1 Trauma ER equipped with state-of-the-art resuscitation bays.

My ace team, fully assembled and waiting, represents the best and most senior staff in the ER, and we absolutely nail it. We’re calm, we’re in sync, and we provide textbook-perfect cardiac resuscitation using every available drug and modern gadget — and he dies.

Looking back, I’m convinced we couldn’t have saved his life. Here’s a statistic I never learned in medical school: roughly 90 percent of cardiac arrests prove fatal. I had hung my white coat on a fickle scaffold of advanced technology, “wondrous” pharmacology, and masterfully trained people who, at best, could meaningfully help such a patient survive only one out of 10 times. I grew frustrated with these ineffective interventions.

What could have saved him? Prevention. To keep him alive, medical professionals needed to intervene in his life five, 10 or 15 years before he reached the ER.

How did I get to that ER room, and what led me out after the four agonizingly long years of my emergency medicine residency? How did I change my approach 180 degrees to focus on prevention and treating the whole patient? Westmont.

My liberal arts education at Westmont helped pave my path to medicine and then course-correct toward the emerging field of lifestyle medicine. This journey began with my major in biology and the life-changing experience of studying science abroad in New Zealand for a semester. Beyond the scope of my biology books, I gained valuable skills and traits from my Westmont experience that too many of my colleagues in medicine lack:

- Strong and broad scientific understanding

- Critical thinking skills

- Empathy and compassion

- Willingness to challenge dogma

- Holistic approach to knowledge

- Appreciation for multiple perspectives

- All-encompassing, restorative stewardship of God’s creation

My professors encouraged me to question both them and the science and to always critically appraise what I was learning. They gave me a respect for authority yet taught me to think for myself. They focused on more than mastering biology, encouraging me to become a better scientist, human being and citizen of the world.

At Westmont I embraced literature, ethics, religious studies, advocacy and communication, which have all enriched my professional work. I developed an appreciation for pursuing multiple perspectives on a problem filtered through the lens of the best available science and through other disciplines.

Academically, Westmont prepared me well for medical school at USC, yet it also helped me build a personal foundation so I could survive my emergency medicine residency. My faith, which Westmont shaped and nurtured, kept me fundamentally sound.

Secure in my faith and calling, I took my natural aptitude for science, a knack for complex and delicate procedural skills, and a clear command of stressful situations and sought to use these God-given talents to help people. Medicine — and especially emergency care — always seemed like a great and tangible way to accomplish this goal.

However, I quickly realized people in need of my newly acquired trauma care skills represented only a small percent of my patients. In reality I spent most of my time mired in chronic diseases and emergencies related to diabetes, high blood pressure, heart attacks and stroke.

Often, I could do little for these people, as the damage had already been done. Patients spent a lot of money, and I expended precious physical and emotional capital on emergency treatment that amounted to little more than damage control. Often, they were like the fire chief, on the wrong side of our dismal statistics for treating some of our most common chronic diseases. The more I learned about the evidence (or lack thereof) behind the treatments I had available to me, the more disenchanted I became about our medical system.

I also understood that many people arriving in the emergency room lacked access to routine primary care. Thinking that might be the missing piece — and hoping to save my personal investment in emergency training — I returned to New Zealand, where I’d spent a wonderful semester as a Westmont student, getting to know the people and culture. I worked in an emergency room at a large hospital where all residents have access to primary care, taking my first tentative step toward a more holistic approach.

One of my early New Zealand patients was a woman in her mid-to-late 40s who passed out at her dining room table due to a stroke — a massive brain bleed. I did everything I could for her, but few people survive this type of hemorrhagic stroke. I had to remove life support and inform her husband and eight children, ages 2 to 18. I’ll never forget the look on the 18-year-old’s face as he held his 2-year-old sister. His life and that of his family had completely and unexpectedly changed that night over dinner. I was utterly devastated and frustrated about this loss of life. In fact, her life, and lifestyle, needed to change long before that night. Unfortunately, she lived in a society, much like ours, where cultural norms, economics, political pressure and convenience make healthy choices difficult.

With access to free primary care, this woman saw doctors regularly who prescribed medicine for her blood pressure. Yet she needed much more than that. The medical community had to go deeper and address factors such as access to healthy food, an environment conducive to a sedentary lifestyle, and a frenetic pace of life antithetical to rest and sleep.

I returned to the United States after almost two years as a steadfast proponent of practicing medicine in a radical yet profoundly simple new way. I also took to heart the Westmont notion of the liberal arts as a life-long pursuit, earning a master’s in public health and completing a second residency in preventive medicine and public health at UCLA. A Lifestyle Medicine Intensivist Fellowship at Loma Linda University led me to stay on as a professor and eventually serve as assistant director of the lifestyle medicine fellowship. I sought to better understand and address the chronic disease epidemic in our country and in my patients while also becoming a better person, physician, leader and healer.

Now that I’m out of the resuscitation bay, whom do I treat, and how do I help them heal and thrive?

I practice lifestyle and preventive medicine inside a culture of chronic disease. Two-thirds of U.S. adults suffer from at least one diagnosed chronic disease; almost half suffer from two or more.

Lifestyle medicine uses therapeutic lifestyle interventions, such as diet, exercise and sufficient sleep, as a primary way to treat these chronic conditions.

The No. 1 cause of death in the United States is heart disease, followed by cancer. COVID-19 has become No. 3 (the co-morbidity link to pre-existing chronic disease is stunning), while six of the next seven causes of death echo back the tragic reverberations of chronic disease.

Most chronic diseases stem from unhealthy lifestyles, as the top 10 risk factors for chronic disease and death illustrate:

|

1. Poor diet |

2. Tobacco use |

3. High blood pressure |

4. Being overweight or obese |

5. Insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes |

|

6. High cholesterol |

7. Impaired kidney function |

8. Alcohol and drug use |

9. Air pollution |

10. Low physical activity |

Nine out of 10 of these risk factors relate directly to our lifestyle, with air pollution being the lone exception. The largest environmental factor by far affecting our health is the food we choose to eat. Surprisingly, diet has surpassed tobacco use as the No. 1 risk factor for death and disease. I believe changing our food systems and eating patterns represents the greatest public health challenge of our generation, just as the previous generation focused on decreasing tobacco use.

Poor lifestyle choices and environmental exposures account for about 75 percent of the risk of developing most chronic diseases; genetics represent only 25 percent. Changing our lifestyle can lead to a cure. Emerging evidence in the field of epigenetics (the study of gene expression) indicates that lifestyle choices make a profound impact on how our body turns genes on or off, so a healthy lifestyle can overcome even risky genetics.

Why does lifestyle medicine differ so greatly from widely accepted medical practices?

In the early 20th century, infectious dis-eases represented the leading causes of death. But both clinical and public health medicine made incredible progress. Clean water, vaccines and antibiotics revolutionized medical care and drastically cut the risk of infection. This success led medicine into a

pharmaceutical age. After curing infections with a few simple pills, doctors sought to treat non-infectious diseases the same way. But most chronic diseases lack a single root cause that responds to medication; poor lifestyle choices lead to chronic disease. When medications failed to be the panacea for chronic diseases that antibiotics were for infections, doctors switched priorities from curing them to managing them. They relied increasingly on multiple prescribed medications, each treating one specific disease or symptom, as well as on procedures and technology. Unfortunately, these methods have proven to be reactionary, expensive and ineffective.

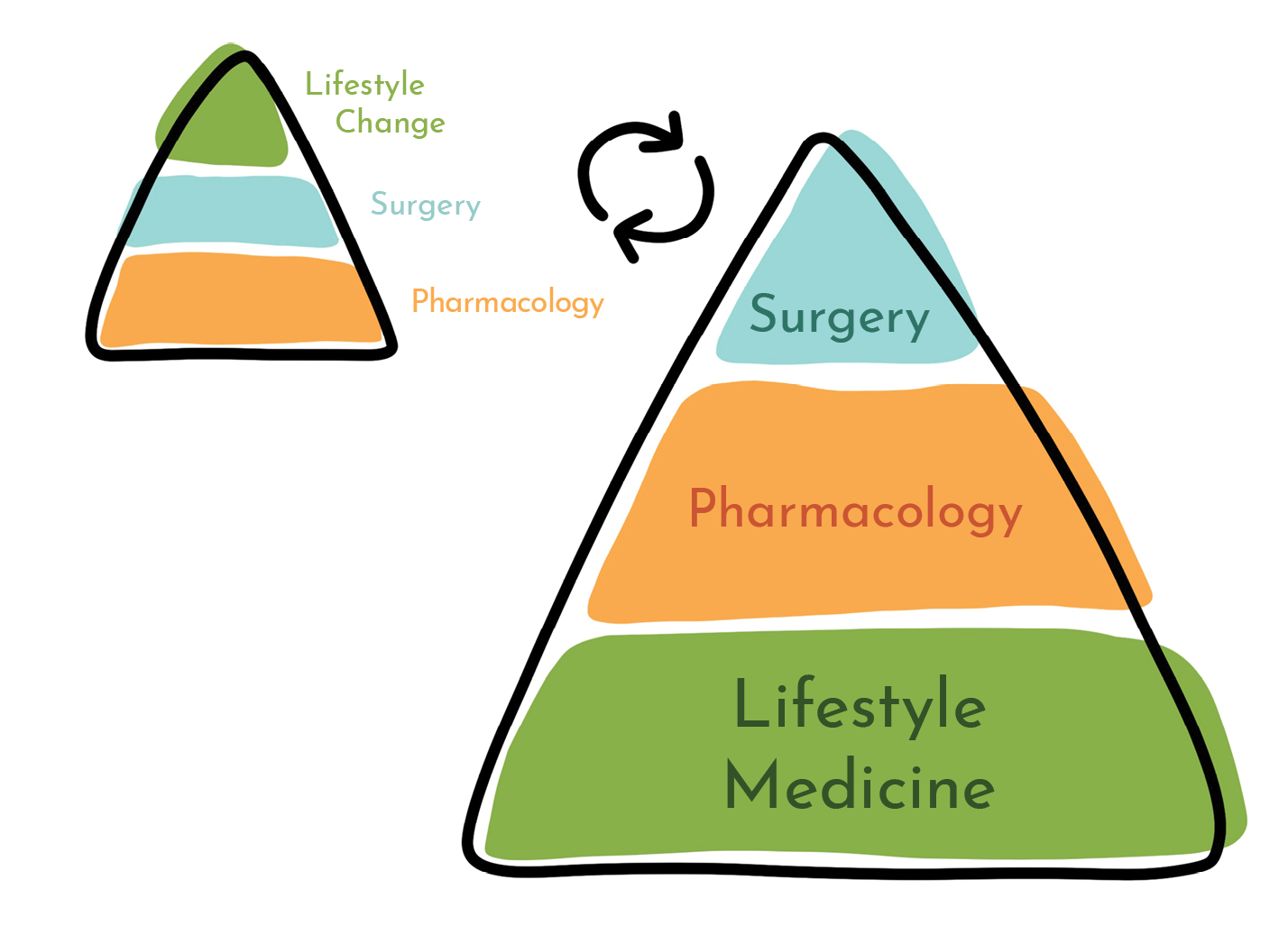

An illustration depicts the typical approach of modern medicine: Imagine a pyramid where each successive layer represents the weight and priority of time and resources dedicated to a specific chronic disease. The pyramid features a large yet shaky base representing pharmaceuticals, a smaller though prestigious and expensive block in the middle for surgery, and a tiny tip at the top for lifestyle changes when all else has failed and doctors aim for a gentle and quiet end.

When we try to apply this model to chronic disease, we encounter problems. For example, we identify insulin resistance as the root cause of diabetes. Medication manages the symptoms of this condition and may slow its progress, but it doesn’t cure it. We’ve given up looking for a cure and settled for control.

Why can’t we cure chronic diseases through traditional pharmacologic means? They fail to address their causes rooted in poor lifestyle. We spend 75 percent of the pyramid ignoring that 75 percent of our root causes stem from lifestyle choices.

Lifestyle medicine flips the pyramid. Now surgery sits on the small top (surgeons can call it the penthouse), pharmacology occupies a shrinking middle, and lifestyle medicine provides the strong foundation as the standard of care. Some patients will continue to need medication and surgery, but these practices should merely support the foundation of a healthy lifestyle. An ounce of prevention through lifestyle is truly worth a pound of cure.

Flipping the pyramid requires a revolution. We need to start changing society and the exposures that threaten our health. We must address food and housing insecurity and the social aspects of health. In fact, we need to put social and behavioral determinants of health at the foundation of the pyramid, below lifestyle medicine, pharmacology and surgery.

In the United States, 90 percent of our health care dollars go to treating chronic disease. We spend a lot — $3.3 trillion each year — on health care. This equals 18 percent of our gross domestic product (GDP), more than we spend on the military. By 2050, Medicare and Medicaid alone will likely represent 20 percent of GDP. Making inroads here would create significant cost savings. However, as medicine becomes more corporate and profit-driven, there’s less financial incentive to change this rampant spending, endangering our health and wellbeing.

Lifestyle medicine is progressive, inherently cheaper and builds on six core pillars: a whole-food, plant-based dietary pattern, regular physical activity, restorative sleep, stress management, avoidance of risky substances, and positive social connection. These practices provide the primary therapeutic approach to treating and reversing chronic disease. I add a seventh pillar to my professional practice: a healthy spiritual life. Our spiritual, physical and mental health are intricately related, and all must be healthy for us to thrive.

Modifying our lifestyle requires a new medical skill: de-prescribing! We’ve had to learn how to safely eliminate the many medications our patients have been taking once the body starts to heal. What a major shift for medical professionals who’ve been taught to prescribe their entire careers. We can put diseases in remission and even cure some of them, leading to a decrease in mortality and morbidity, a better quality of life and less money spent on health.

How can you reduce your risk for most chronic diseases and cancers by 70 to 90 percent and avoid the invasive and unnecessary indignity of the ER resuscitation bay?

Follow the seven pillars of lifestyle medicine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We know lifestyle medicine works because the people around the world who live the longest and have the best health practice it. National Geographic identifies the areas where these populations of centenarians live as “Blue Zones”: Sardinia, Italy; Ikaria, Greece; Okinawa, Japan; Loma Linda, California; and the Nicoya Peninsula, Costa Rica.

For example, Sardinia, Loma Linda and Okinawa all feature a strong family social unit, no smoking, regular physical activity, robust social engagement, and a 90-95 percent plant-based, unprocessed diet. Adopting such a diet is a great place to start improving your health.

Lifestyle medicine recognizes food as medicine and prescribes it as a treatment. Poor diet represents the leading cause of chronic diseases, and it’s the best way to start reversing them. An unprocessed, plant-based diet can reverse damaged arteries and heal heart muscle within months and manifests powerfully when sustained over years, although some scarring may remain. When cancer patients follow plant-based diets and exercise regimens as additional treatments to surgery and chemotherapy, studies show they prolong their lives and improve their quality of life during treatment and beyond.

Lifestyle medicine empowers patients to assume responsibility for their health and leads to meaningful and relational exchanges between providers and patients, with patients becoming the pilots and doctors the copilots. This evidence-based approach focuses on holistic health and incorporates all areas of our lives. It’s collaborative and multidisciplinary and encompasses many perspectives. It’s also inexpensive and accessible. It’s a liberal arts approach to health. My vocational calling to lifestyle medicine embodies my educational legacy from Westmont.

So where does lifestyle medicine go from here? Where do I go from here?

About 30 medical specialties and various health care providers can now pursue certification in lifestyle medicine, and all work together to improve our health and wellness through critical thinking. Ranked as one of the five fastest-growing medical specialties in the United States, the field has seen 700 percent growth in membership in the last few years. So many of us in health care think our system is broken, and health care workers are burning out at alarming rates. Lifestyle medicine serves as a beacon of hope that we can remake medicine as evidence-based, centered on whole-patient and preventive care and truly multidisciplinary.

Special-interest groups that profit from the old approach will always push against this new paradigm. Seeing health as a holistic mindset represents a necessary shift in dogma that takes account of the interconnectedness of human health and planetary health.

To date, given the unfortunate state of insurance coverage and reimbursement rates affecting viable business models, mostly middle- and upper-class people have benefited from lifestyle medicine. But historically disadvantaged populations need it the most.

My dream is combating this inequality by creating an intensive lifestyle-change program accessible to everyone, so as many people as possible can thrive with optimal health and well-being. I seek to create a faith-based, culturally sensitive and multi-lingual curriculum adapted to multiple settings, such as a retreat center, a college campus, a medical practice, a church or community center, a home group or a virtual setting.

I seek to foster in my Westmont students a similar lifelong passion for becoming better learners, image-bearers, and perhaps future doctors, nurses and health care providers oriented toward lifestyle medicine ready and equipped to find and flip pyramids.

Dr. Sara Johnson earned a bachelor of science in biology at Westmont in 2005 and graduated from the Keck School of Medicine at USC in 2010. She completed a master of public health in health policy and management at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health and holds board certifications in emergency medicine, preventive medicine and public health, and lifestyle medicine. She is one of only a handful of physicians to complete a Lifestyle Medicine Intensivist Fellowship. She serves as the assistant program director and faculty editor of the Lifestyle Medicine Residency Curriculum, a national joint project of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine and Loma Linda University. She applies research on lifestyle medicine in the clinical arena and teaches biology at Westmont.