Westmont Magazine How Loving Attention and Meaningful Conversations Help Us See and Connect Deeply with Each Other

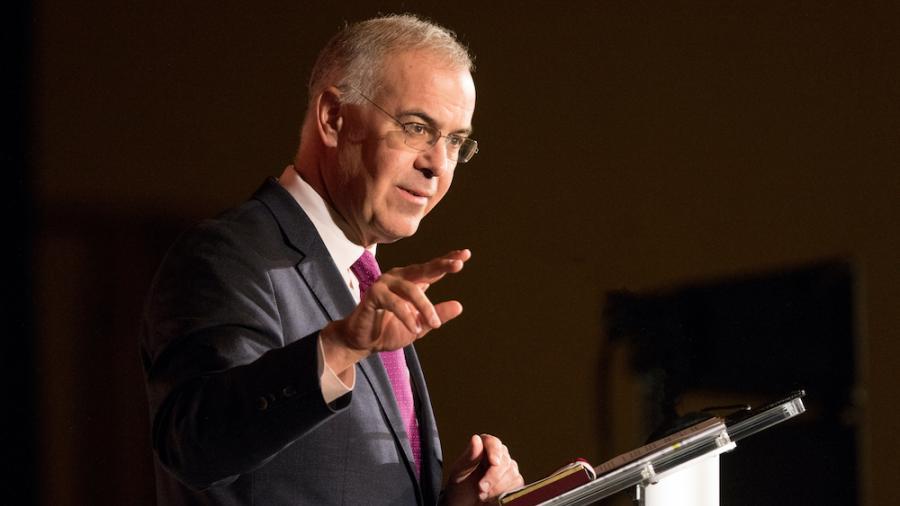

Notes from a talk by New York Times columnist and bestselling author David Brooks at Lead Where You Stand in June 2021.

A few years ago I wrote a book called “The Second Mountain” about going through the valley and building a second and better life after it: post-traumatic growth. We’re beginning to get back to normal after the pandemic — we’re taking off the mask. How do we think about the next chapters of our lives? The saddest people in life are those who just live day by day. The most fulfilled divide their life into chapters.

An army captain and his wife do a personal retreat every time they get a new assignment. They reconsider everything. Are we happy with the Army? Are we happy with our marriage? Are we happy with the way we’re raising our children? People who focus on the chapters are more intentional and avoid regrets.

The lock-downs, isolation and distancing have felt like a moral problem. So much of our sense of purpose comes through small acts of hospitality. Without those, I felt a little drift in my sense of purpose, and it produced what a colleague of mine called languishing: a feeling of joylessness and aimlessness. That was exacerbated by a loss of power — COVID had the power. We didn’t have freedom, and our society has mixed-up views about freedom. We too often define it as absence of restraint: I can do whatever I want. But a better way to think about freedom is the capacity to imagine different futures and the ability to realize them. That’s a richer freedom. If you want the freedom to play the piano, you have to chain yourself down to practice day after day. Sometimes it’s the chains you choose that set you free. Negative freedom leads to license, and you become a slave to your own passions. Positive freedom needs discipline and commitment.

Now that we’re getting more power back over our lives, how do we use it? It’s a three-step process. First, you have a hard time. Second, you tell a story about what you experienced to find the meaning. Third, you change your life to reflect the new reality. I asked my readers in the New York Times to share moments that turned their lives around. They often pointed to a hard time. Greg from Brisbane, Australia, wrote about the death of his wife of 21 years from a brain tumor. “A sense of personal growth, awakening and understanding has come to me from this experience and from reflection and inner work to a point that I feel almost guilty about how significant my own growth has been as a result of my wife’s death,” he says. “In ‘The Hidden Wholeness,’ Parker Palmer writes about the two ways in which our hearts can be broken: shattered and scattered or broken open. The second image is a heart broken open with a new capacity for both our own and the world’s suffering and joy, despair and hope. The image of a heart broken open has become the driving force of my life in the years since my wife’s death. It has become the purpose of my life.”

In these moments of formation, you can’t solve your new problem with the same level of consciousness you have to address your old ones. It’s a challenge to get bigger. It’s a challenge to go through the suffering and disorientation to find a deeper version of yourself. Suffering carves into the floor of the basement of your soul and reveals a cavity below that, and then it carves through that and reveals a cavity below that. And when you see into the depths of yourself after a period of disorientation or suffering or dislocation, you realize that only spiritual and emotional food will fill those depths. You search for something, what C. S. Lewis called the scent of a flower we’ve not yet found, the echo of a tune we’ve not yet heard, news from a country we’ve never visited. You’re drawn by some force to be bigger and to find a bigger way of living. The gentleman from Australia described it as broken open. It’s a vulnerable way of living. You surrender to greater loves. It’s also a sense that you’re going to lead a more meaningful life, that you take a stand in the eternal battle between good and evil, between love and hatred. It’s the only drama we really live with.

Augustine pointed out that we all love a lot of things. But some desires are higher than others. The first goal is to order the desires of my heart, which leads to profound questions. What do I want more than anything else in the world? What is the ultimate truth? To what do I surrender? What am I doing when I feel most alive? What is my ultimate desire? The second goal is to prioritize my calendar according to my loves. How you spend your days is how you spend your life. The third goal for me is to grow deeper in my faith, which has suffered during COVID. It has become a set of ideas and maybe something to watch over Zoom and some music to listen to on the headphones, but not a behavior. Faith is not an ideology; Jesus is a way.

We entered COVID with a crisis of division, loneliness and isolation. People told me they feel invisible, and a majority of Americans told pollsters no one understands them. My experience as a reporter was of people feeling unseen and unheard, Black people feeling their daily experience was not seen by white people, real people feeling unseen by coastal elites, depressed young people not feeling seen or understood, employees feeling invisible in organizations and at work.

This sense of feeling invisible and disrespected was at the root of a lot of our social anger, and COVID made it all worse. Suddenly we started wearing masks, but before the physical masks, we were putting on all sorts of psychological and emotional masks — permissions to be distant and hidden. Now we have an opportunity to unmask ourselves. It takes skill to see each other. There’s one skill at the center of every successful company, college, family and nation: the ability to see others deeply and make them feel deeply seen. Our society lacks this skill.

If you’ve ever felt seen, you’ve probably had a transformational moment in your life. It’s a moment of breaking open when somebody really sees you, and you feel you’ve been honored. This is the moment of connection; this is how you create a company where people feel valued. How do we develop this skill? It starts with a way of paying attention, a way of seeking to know another person. In the Bible, the word “to know” means a lot of things, and it’s not just a cognitive process. It means to study but it also means to enter into covenant, to be emotionally bonded with. It’s projecting forth a loving form of attention, a gaze that supposes each person is made in the image of God. A person who can see others this way approaches everybody with a spirit of loving inquiry and being amazed. C. S. Lewis said that if we had never met a person and then met one, we’d be inclined to worship such a creature because people are so amazing. A hero of mine called this illumination as God illuminates us into being with his love. It’s a kind of seeing that expands life. When we approach others with that illumination, we have a sense of really seeing them. And that is just hard. The Bible is filled with images and stories of recognition and non-recognition, of times when people really felt seen and times when they’re not recognized. Being unseen is not a failure of the intellect but of the heart.

The act of projecting loving attention is the first part of seeing someone. The second is curiosity, asking questions about people. A friend named Dan McAdams studies how people describe the story of their life. He pays people to sit for hours and tell the story of their lives. They almost always cry at some point, and they refuse payment, saying it was one of the most enjoyable and fulfilling afternoons of their lives. They say that no one ever gives them the opportunity to tell their stories. People are hungry for that. Then there’s the skill of patience. When you’re getting to know somebody, you can’t push them. You have to go at their pace, and you have to be socially skilled enough to understand the pace to make a connection.

If you want to know another person, you have to ask them questions. It takes skill to run an organization, be a leader and make people under you feel that they are seen, heard and understood, that you have a wider life together. We’re trying to navigate a complex and social world, and our social skills are not adequate for the world we now inhabit. We didn’t evolve to live in a complicated world with hundreds of ethnicities. Most of human history has been pretty coherent, but now we have diversity and pluralism — I’m personally glad we do. But it takes a higher level of social and conversational skills. We’re not as good at seeing others and understanding each other as we think we are. Research shows that most people are right about others 20 percent of the time, and they’re wrong 80 percent of the time. When you’re trying to get to know someone, you have to master the skill of conversation.

What are the skills of a good conversationalist? First, treat attention as an on-off switch, not a dimmer. Rather than thinking about how we’ll respond, we need to give people 100 percent of our attention. We need to be comfortable with the pause that occurs when someone is finished talking, and we’re thinking about what to say. Second, be a loud listener, a responsive listener. Use the midwife model; you’re not giving birth yourself, you’re helping the other person give birth to an idea. If someone tells you a story that’s important to them, they probably left out essential details. So ask questions about the details. It’s useful to go back and say, “I hear you saying this,” so you clarify what the other person means. You get a much richer set of interactions. When we disagree about something, there’s always something we agree about underneath; keep that at the center. And if you’re in a disagreement, keep coming back to what you agree on. That’s a way to save the relationship. Finally, find the disagreement under the disagreement. If you’re disagreeing about something, ask why do we disagree about this? What foundational principle causes us to disagree? You enter a joint exploration to find the disagreement deep down.

The second skill in getting to know someone, deeply connecting and having a serious relationship with them, is asking the right questions. The quality of your presence in the world will be determined by the quality of the questions you ask. I like to ask people how they got their name. What is a great memory from your childhood? People love talking about this stuff. Couples love talking about how they met. A deeper question is asking someone what they would do if they weren’t afraid. What crossroads are you at? These kinds of questions are honoring. A good way to close down conversation is to ask closed-ended questions or evaluative questions: Where do you go to college and what neighborhood do you live in? These are ways of measuring people. A good way to start great conversations is to ask open questions that don’t lead the answer in any particular direction. They just open up possibilities: how did you, what’s it like to, tell me about a time when. If you died tonight, what would you regret not doing? If we meet a year from now, what victory will we be celebrating? Focus your questions on the important things. These questions can open up relationships and make people feel seen.

This leads to a final skill: creating organizations where people feel seen and deeply connected, where the whole person is welcome and the broken-open person who wants to lead a deeper, wider, more relational life can thrive. We’ve seen organizations that change people and some that don’t, where people just pass through. But schools like Westmont leave a residue on people. You can always tell a Marine; the institution leaves a mark on them. These institutions are not just getting their employees to do work, they’re building a human being by setting certain standards of how to be, certain excellences.

How can you tell whether an organization helps people feel seen and connected? How can you tell whether they’re “thick,” where people throughout the organization share its values and customs, or “thin,” where few embrace the culture. Thick organizations have a set of collective rituals that bring out the sacred every day. They have shared tasks where people are watching each other closely. They tell and retell sacred origin stories about themselves. They incorporate music with daily life because it’s hard to be distant from someone you’ve danced with. They’re not afraid to be themselves; they have a distinct culture — there’s not any other place quite like it. My wife, Anne Snyder, who edits Comment Magazine, wrote a book, “The Fabric of Character: A Wise Giver’s Guide to Supporting Social and Moral Renewal,” after touring thick organizations. She identifies 16 questions you can ask about your organization to determine if it’s thick or thin, whether it can help revive character and transform lives.

As we get a chance to relate to each other while we reconstitute our communities and organizations after COVID, I hope we do it on a deeper level — on a broken-open level. Going to that deeper level involves a quality of attention, a loving embrace of other people. But it also involves concrete skills of how do you carry on a conversation, how do you structure a meeting so people feel seen, how do you create a culture where people can thrive.

As you get back power from COVID, you have an opportunity to reconstitute your organization, your leadership style and yourself. This is a moment when the whole world, having gone through hard times, has a chance for rebirth. The question is: Will we take advantage of this opportunity?