Westmont Magazine My Front-row Seat to a Miracle

Tom Byron and the Hawaii Game

By Don Volle '73

“Westmont College captured two victories last Friday, February 4: a man’s victory over death and the greatest basketball win in the history of the college.”—from a Horizon story by Dave Raney ’73

Nearly 50 years ago, Westmont won an improbable victory by defeating the University of Hawaii’s nationally ranked basketball team. This historic moment came just a day after the death of Coach Tom Byron, the men’s basketball coach and a beloved dean of students.

I served as the student manager for the team that year. We began the season 10-0 and then traveled to play Cal State Northridge. While the players were warming up, I walked into the locker room and discovered Coach Byron lying on a training table in obvious discomfort. I knew that what we feared was true: His cancer had returned. Coach Byron made it to the bench just in time to coach what would be his final game, a 72-59 loss to the Matadors.

Two years earlier, I came to Westmont hoping to play basketball for Coach Byron. My dad, Art Volle, was dean of students at Wheaton College, Byron’s alma mater. He knew Tom well as a star athlete and student leader. Byron later returned to Wheaton as a faculty member and worked with my dad in the Student Personnel Office. In 1965, Byron accepted a position as head basketball coach and athletic director at Westmont.

While not recruited to play basketball, I had a great experience playing on the freshman team for Ron Mulder ’61. At the end of the season, Byron stepped down from his coaching duties. The following October, he was diagnosed with a malignant mass in his lung and had an entire lobe removed, nearly 10 years after treatment for melanoma.

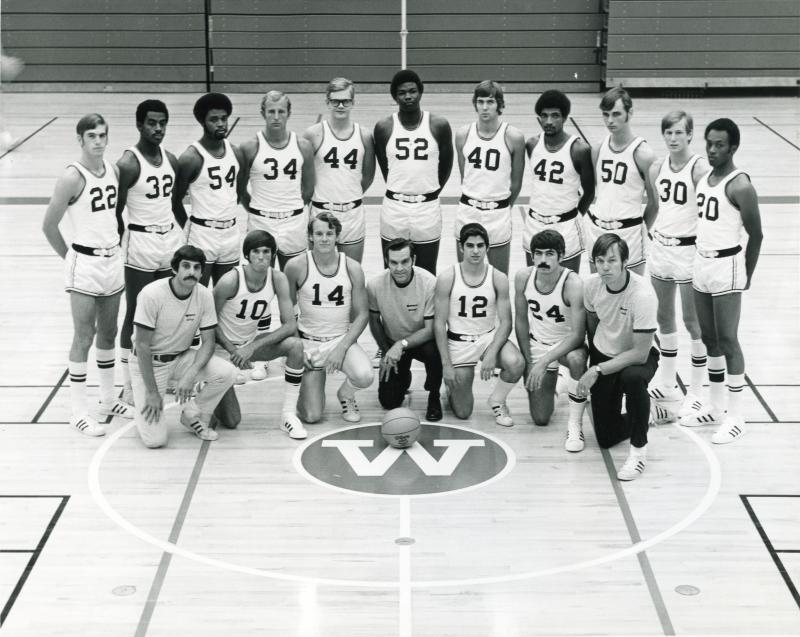

In May 1970, Jim Larson became the new varsity basketball coach. He inherited many talented returning players and recruited some standouts of his own: Andrew Hill ’73, Charles Anderson ’72 and Fred DeVaughn ’73. I earned a spot on the varsity team, but by the end of the season, I knew my playing days were over. A few weeks later, we were shocked when Larson accepted a position as head coach at Cal State Bakersfield.

Meanwhile, Byron received more bad news. Exploratory surgery revealed several large, inoperable and malignant tumors on his liver. Doctors said he had eight weeks to a year to live. An ordained Baptist minister, Tom had a deep faith. He and his wife, Dorothy, asked some close friends to come to their house and pray: Bryan Leech, Tom’s pastor at Montecito Covenant Church and Westmont colleagues Lyle Hillegas and Rusty Springer. The group anointed Tom with oil and prayed for healing. Dorothy later remembered the gathering as a powerful and transformative experience.

Soon after, feeling well and claiming healing, Byron asked for his coaching job back. Westmont quickly obliged. He continued feeling healthy throughout the summer and fall. Shortly before the basketball season began, Byron asked me to be team manager.

We began the 1971-72 season with three impressive wins. Then we faced Wheaton College in the opening round of the first ever Maroon and White tournament at Westmont. A few years later, the college changed the name to the Tom Byron Classic, which continues to this day.

Following a 110-81 win over Wheaton, Westmont knocked off its next six opponents before losing the game in Northridge. The following day Byron checked into Cottage Hospital for palliative care. Mulder moved up from the freshman team and coached the varsity with Byron’s assistant, Dave Bregante ’70. Finding it difficult to focus on basketball, the team lost four of its next five games.

During a somber time on campus, professors prayed for Byron in class. Students set up a 24-hour prayer vigil in the Nancy Voskuyl Prayer Chapel. Tom invited each of his players and coaches to visit him alone at the hospital. Dave Bregante recalls him praying for the team instead of being concerned for himself. Tim Walton ’72 and Charlie Mehl ’73 both said Byron ministered to them rather than the other way around. Ron Mulder describes his final visit as “a healing experience that was God’s gift to me.”

On February 3, we felt stunned disbelief and sorrow when we learned that Tom Byron had died early that morning. He was 42 years old. That same day, Mulder became acting head coach. With a team already in disarray and devastated at the news about their coach, he had a tall task preparing his players for a game with the University of Hawaii Rainbows the next day.

Hawaii was arguably the most formidable opponent Westmont had ever faced. They came into the game boasting a 16-1 record and were the 14th ranked NCAA Division I team. They had already achieved extraordinary wins, including two victories over Florida State, which later narrowly lost the NCAA championship game to John Wooden’s UCLA team. Three of Hawaii’s starting five — still known in Hawaii as the Fab Five — wound up being drafted by the NBA. Bob Nash, a 6’8” power forward averaged 19.1 points per game and was the nation’s sixth leading rebounder. The Detroit Pistons drafted him in the first round, and he played in the NBA from 1972-1979.

The morning of the game, Nash taunted Bregante: “Tell that Fred DeVaughn of yours I’m going to eat him alive tonight!” Listed at 6’8” and 225 pounds, Fred had compiled some impressive statistics of his own, averaging 15.4 points and 13 rebounds per game. He later became a two-time NAIA All-American. The Houston Rockets drafted him and signed to a contract. He played professionally in Europe for six years. Bregante, a master of motivation, relayed Nash’s message to Fred word for word. Game time finally arrived.

Shortly before taking the floor, Westmont’s players dedicated the game to Coach Byron. A standing-room only crowd packed Murchison Gymnasium. A moment of silence honored Coach Byron. His daughter Annie, then an 11-year-old, said it was her keenest memory of the entire evening. She recalls thinking a gym that full could never be completely silent — but it was. “I was shocked,” she said. “It was an incredible experience.”

Soon after the opening tip-off, Hawaii displayed its up-tempo, free-flowing style. From my front-row seat next to the coaches, they appeared bigger, faster, stronger and more athletic. Jerome Freeman of Hawaii knocked down 10 straight points on amazing drives and perimeter shots. We suddenly found ourselves down by 16 points: 39-23. The capacity crowd was nervously quiet. Westmont looked outmanned, discouraged and defeated. We finished the half with a small run and headed into the locker room down 51-40.

During the break, Mulder and Bregante switched strategies. They changed our defense from zone to man-to-man. Just before heading back to the gym, Tim Skelley ’73 reminded the team we were only down by 11 points. “Hey,” he said, “We could still win this thing!”

In the second half, we looked like a completely different team as we reeled off eight unanswered points, making the score 51-48. A few minutes later, a jump shot by Brian Kerkering ’72 gave us the lead. We outrebounded Hawaii. We outshot Hawaii. We outhustled Hawaii. Their offense suddenly seemed stymied. We kept pounding the ball to DeVaughn, who scored with layups, hook shots and inside jump shots. When Fred wasn’t scoring, the rest of the team was hitting outside jump shots. With less than eight minutes remaining, Westmont led 75-66. The crowd went berserk.

But Hawaii fought back and tied the game at 85 with only 1:09 remaining. Andrew Hill put Westmont back on top 88-85 with three straight free throws. Freeman responded with a 15-foot jump shot, making the score 88-87 with just 27 seconds left. Dave Raney described the final seconds in his Horizon story: “The crowd was pounding. Doug Franklin, triple teamed on the sideline, calmly dropped a pass to DeVaughn, who was wide open under the basket: 90-87. Holiday’s meaningless shot with one second to go made the final score 90-89.”

When the final buzzer sounded, unbridled exuberance, pandemonium, mayhem and joy exploded as the crowd spilled out onto the floor. The overwhelming emotion on campus during the past few weeks created an indescribable depth of feeling.

Years later, Westmont philosophy professor Bob Wennberg told basketball coach John Moore ’78: “Aside from the marriage to my wife, it was the most exciting moment of my life.”

The front-page headline on Saturday morning’s Santa Barbara News-Press proclaimed: “Westmont Wins One for Byron: Warriors Upset 14th-Rated Hawaii.” While calling Fred DeVaughn’s performance of 34 points and 22 rebounds “great,” Coach Mulder gave credit to the entire team: “Everybody contributed to the win. It was truly a team effort tonight.” The headline for the Horizon story quoted Westmont track coach Jim Klein: “It was a festival, a celebration.” Raney wrote, “The Westmont community became a body in a new way... and the feeling we all had was more than you can express by saying 90-89. It was a time of unity and rejoicing — a time of realizing we did not have to mourn.”

That same weekend a second overflow crowd gathered on campus for Byron’s memorial service in Page Hall. Members of the basketball team served as ushers and handed out programs. The Westmont choir sang “Be Still My Soul.” Tim Skelley spoke on behalf of the basketball team. Bryan Leech gave the meditation, aptly titled “The Bitter and the Sweet.” English professor Arthur Lynip delivered the closing benediction.

The basketball team finished the season 21-9. We won the school’s second District 3 championship and a trip to the NAIA National Tournament in Kansas City. In our first game, we beat Edinboro University of Pennsylvania 91-72. We then faced our second toughest challenge of the season. Xavier of Louisiana averaged more than 96 points per game led by two future NBA players: Donald “Slick” Watts and Bruce Seals. We won 71-59, holding Xavier to its lowest point total of the year. Our season ended with a 72-62 loss to Stephen F. Austin.

Nearly 50 years have passed. To this day, Fred DeVaughn says his experience with Coach Byron was an important turning point in his life. At the height of the Civil Rights movement, DeVaughn transferred to Westmont from Morehouse, an all-male Historically Black College in Atlanta, Georgia. Martin Luther King Jr. graduated from Morehouse and was a classmate and friend of Fred’s father, also a Morehouse alumnus.

Fred’s sister Pauletta DeVaughn Mayeroffer ’73 and close high school friend Ron Coleman ’72 convinced DeVaughn to transfer to Westmont. Arriving at the predominantly white campus was a culture shock for him. Fred credits Byron’s unwavering consistency and expectation of excellence with helping him make this transition. Their relationship extended past the court, and each of them learned from the other. “Coach Byron changed my life,” Fred says. “When I found out Coach Byron had died, I had to keep my emotions in check. I had a job to do. I knew I was being used for greater purposes. I’m so glad that the Lord was able to use me at that precise moment in time.”

I often find myself pondering these events. Philip Yancey says that God sometimes seems distant, silent, hidden. Sometimes God feels close, caring, loving. The Westmont community experienced both feelings in one unforgettable weekend. And still I have questions. Why does God seemingly answer some prayers and not others? Why are some healed while others are not? Does God really care about the outcome of a basketball game? For one night at a small college in the hills of Montecito, it sure felt like it. I know one thing for certain: I had my own front-row seat to both the mystery and wonder of it all.

Photos courtesy of the Westmont Archives