Westmont Magazine Remembering Rath

by Crystal Nelson Downing ’74

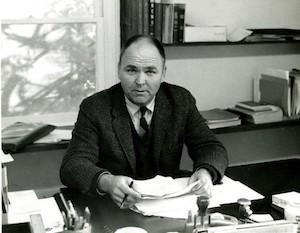

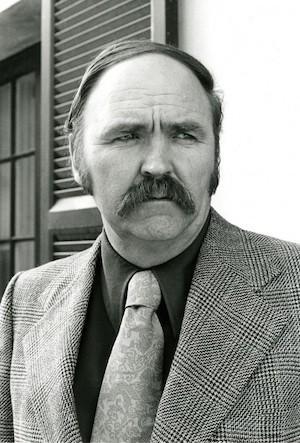

In Memory of Rathburn Shelton (1923-2012)

I am who I am today because of Rath Shelton. Though his spirit has moved on, it continues to live on, and I want to acknowledge how his spirit moved me.

I have only vague recollections of Rath during my undergraduate years at Westmont College, but even then he struck me as someone who made a comb-over look dashing. And there was something about that paintbrush mustache—more like two or three paintbrushes—that captured the artist in him. So it was with delight, several years after graduation, that I accepted a job as his secretary in the Westmont College Alumni Office. There I discovered what everyone discovered about Rath: he was an indefatigable raconteur. My favorite stories were from his years playing trumpet in a big band troupe, stories he would deliver with panache while moving his fingers up and down in front of his face, as though playing “air trumpet.” If I had the power to coin a new word for the English language it would be “rathconteur,” for nobody could do it better.

It was Rath’s serious side, however, that affected me the most. One telling moment happened early in my tenure as his secretary, when an older man pawed me during a college event. After Rath found out, he confronted the man, telling him to never harass me again. Though I wasn’t there, I have always conceived of the confrontation in the form of a film scenario, Rath grabbing the guy by the lapels, pushing him up against a wall, feet dangling, while he lectured him nose to nose.

Of course, as alumni director, Rath had to be more subtle than that. But I did see him push someone against a wall metaphorically. We had traveled to Los Angeles to have lunch with a donor in the exclusive club to which he belonged: a club so discriminating that it had only recently accepted African-American and Jewish members. Not wanting to unnerve me beforehand, Rath only told me afterwards that the club still didn’t allow women. That’s exactly why he asked me along, informing the donor that it was imperative his secretary accompany him. My very presence, then, was a pluck at the club-member’s lapels. The push against the wall came during the lunch conversation. The donor told us about a business he owned and how the illegal aliens he hired were willing to work for a pittance. “I don’t know how they can afford to eat!” the business-owner exclaimed. As I naively listened, trying my best to manifest fundraiser-esque attentiveness, Rath tilted his head back and said “Really? You must not make much money in the business then.” When the business-owner replied, “Are you kidding? I’m making money hand-over-fist!” Rath nodded with an “Ah” and gave me a sideways glance. Only then did I realize what he had done.

More than any other professor or administrator at Westmont, Rath recognized and encouraged my abilities. Though my husband has lovingly supported all my vocational choices, Rath was the one who pushed me to reach my potential. He trusted me with challenging tasks, elevating me to the status of assistant director of alumni relations after only a year or two as his secretary. Once in a salaried position, I had the freedom to teach a Jan-term course in something the college had never offered—women’s literature—a move that Rath endorsed with enthusiasm, as he did my decision to go to grad school in English.

So I have Rath to thank for where I am today, with three published books and two teaching awards. Furthermore, I think Rath would like where I am today: Messiah College in Pennsylvania. Other than the button-bursting pride he took in his four sons and love for his wife, Peggy, I remember Rath repeatedly praising only two people: Tom Byron and Ernie Boyer. While the Westmont community lives in the reflected glory of Tom Byron, I continue to live in the reflected glory of Ernest Boyer, who graduated from the place where I teach. Decades before I ever heard of Messiah College, Rath would regale me with stories of Boyer, who came from a plain-dress pacifist family in which the women wore head-coverings and the men avoided collars and mustaches. Boyer ended up becoming the U.S. commissioner of education and president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, receiving 140 honorary doctorates in addition to his doctorate. Rath was so impressed with Boyer’s commitment to “servant leadership” that he successfully encouraged Westmont to invite him to deliver a Commencement address.

Hence, when I enter Messiah College’s Boyer Hall, on the way to my office, I often think of a man with an amazing mustache preparing me to work according to the ideals of the mustache- free Ernest Boyer. Rath’s spirit lives on, then, not only in a redeemed Eden with Peggy by his side; not only through his wonderful children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren; but also through his mentoring of a timid twenty-something who became me.

Crystal Nelson Downing ’74, distinguished professor of English and film studies, teaches at Messiah College in Pennsylvania.